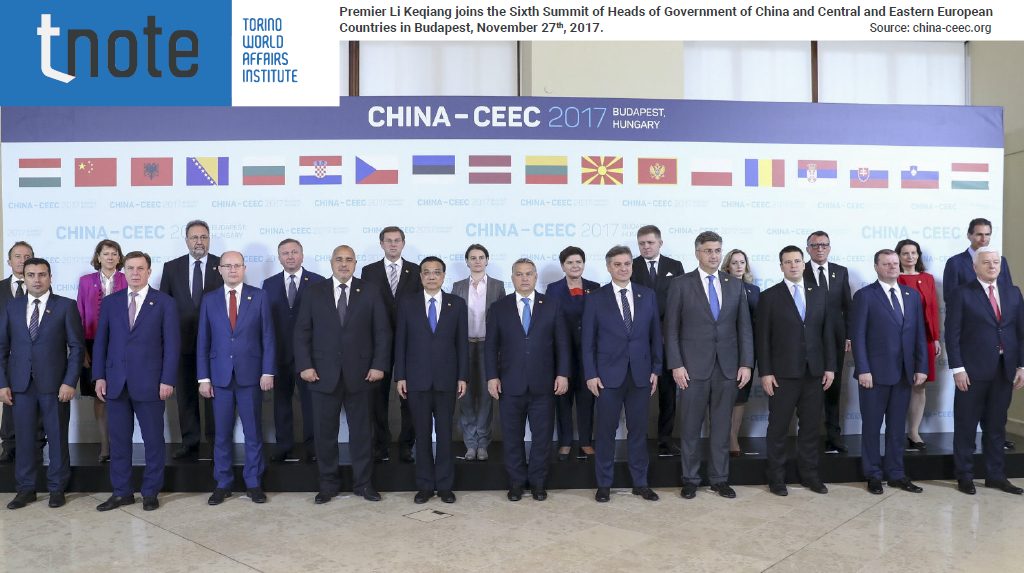

On November 26-27, the Sixth Summit of the Heads of Governments of China and the sixteen countries of Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe (CESEE or “Central and Eastern European Countries”, as China calls them) took place in Budapest, marking the fifth anniversary since the establishment of the 16+1 platform. The meeting itself was business as usual – prosaic speeches, announcements of new projects and signature of agreements. At the same time, unlike in the past, this Summit gained unprecedented coverage in international media, with skeptical and critical takes on China-CESEE relations dominating the discourse. Some of these reports argued that for all the noise about 16+1, the outcomes of the cooperation have been few and far between.

This was not the first time for people to raise such question. After all, for many the China-CESEE relationship is an obscure one. And those who are involved in it, however, become impatient to see a substantial change, in the first place in terms of increase of Chinese investments in the region. Even though the CESEE countries had barely any relationship with China until only a few years ago, the establishment of 16+1, the announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the exposure to China’s growing economic prowess, in combination with their own chronic thirst for capital inflows, has created great expectations. For many, the 16+1 has not yet produced enough satisfactory outcomes.

On the other hand, China seems to have a different understanding of the cooperation. In the aftermath of the Summit in Budapest, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) has published a list of outcomes of China-CESEE relations. The list – arguably a non-exhaustive one – includes 233 items that refer to the policy communication and alignment including signature of multitude of documents that regulate the cooperation, the creation of coordinating mechanisms and institutions, and in particular the interaction between Chinese and CESEE officials, scholars, think tankers, entrepreneurs, media, cultural workers, youth and so on. They are formally divided in five categories, as shown in the table below.

| Category | Number of outcomes | Items included (non-exhaustive) |

| Establishing Policy Communication Platform | 28 | Meeting of heads of governments, other high-level officials, national coordinators, young political leaders. |

| Enhancing Connectivity | 40 | Forums and meetings of working groups on transport infrastructure, logistics, customs policy, internet and communication technologies, signature of agreements, launch of flights from China to CESEE by Chinese airlines. |

| Promoting Economic Cooperation and Trade | 52 | Forums and meetings, fairs and expos, signature of agreements, white papers, emphasis on agriculture, technology and energy (including nuclear). |

| Improving Financial Cooperation Framework | 28 | Agreements and activities involving Chinese state banks, setting up of financial instruments, milestones, AIIB-related activities. |

| Strengthening Cultural and People-to-people Bonds | 85 | Working meetings and establishing networks in education, culture, think tanks, tourism, media, healthcare, local government. |

| Total |

Source: “Five-year Outcome List of Cooperation Between China and Central and Eastern European Countries,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China

The list, as such, answers the question of what are the actual outcomes of the cooperation between China and CESEE countries. The answer, however, at least for the CESEE representatives, may be counter-intuitive. Usually, when discussing outcomes of China-CESEE cooperation, observers expect to see figures on economic exchange, list of investments, perhaps even references to concrete projects (i.e. the Pupin Bridge in Belgrade). In this sense, the list of outcomes presented by China’s MFA leads to a few important conclusions and raises questions pertinent not only to China-CESEE relations, but also in general, to the level of China’s “south-south” diplomacy and regional multilateral platforms.

First, the fact that the Chinese MFA lists all kinds of high-level meetings, including the annual summits, suggests that for China the mere establishment and the development of the 16+1 platform itself are particularly important outcomes. Before the establishment of 16+1, China’s relations with the countries in the region were modest, and there was no multilateral cooperation whatsoever. In the 1990s, and up until the establishment of the 16+1, in many of the CESEE countries, China was seen through the ideological lenses of anti-communism. Rarely someone took China seriously. The fact that China has managed to bring the CESEE countries on the same table, as a convener, agenda-setter, and a recognized actor in the region, therefore, is acknowledged and considered a success by the Chinese MFA.

Second, this lends credibility to culturalist readings of Chinese strategic thinking, according to which building relationships (guanxi) is considered a central element.[1] The fact that the majority of the outcomes listed by the MFA falls in the ‘people-to-people’ category and that in the other categories a significant number of items are actually meetings and forums, backs this assumption. At this stage, for China’s diplomacy, the priority is for CESEE representatives to get to know China, and to be socialized in the setup devised by Chinese institutions. According to the Budapest Guidelines, between January and November 2017 alone, there have been more than 40 official 16+1 events, roughly one per week. Arguably, there have been also other semi-official events hosted by Chinese universities, local governments, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and so on that did not make the official documents – which nevertheless, altogether speaks of the importance of ‘people-to-people’ contact for the way China envisions its cooperation with CESEE.

Third, the Chinese MFA has a rather peculiar definition of what 16+1 is, that may be still unclear to both participants from CESEE and outside observers. 16+1 is considered to be only one out of several channels and/or levels of communication (so-called multi-channel and multi-level exchanges), along with the bilateral level, the level of EU-China relations (for the EU-member states of 16+1), and the level of the BRI. In practice, this means that the global developmental vision is discussed at the level of the BRI, the application of that global vision in the regional context of CESEE and the policy discussion happens via 16+1, and the implementation of concrete projects is then carried out on a government-to-government level – while certain regulatory and strategic affairs are also discussed with the EU. This helps explain why some notable outcomes have been omitted. 16+1 is simply a platform for policy discussion and socialization, whereas economics is a government-to-government affair.

Fourth, in line with the division of labor in Chinese diplomacy, one can also hypothesize that the list of outcomes prepared by the MFA presents only the achievements in the fields that are under the competence of or coordinated by the Chinese MFA itself. The MFA has listed the discussion forums and the official commitments made in terms of economic cooperation, while perhaps numbers on trade and investment are to be sought in publications by the Ministry of Commerce. Moreover, specific details about the advancements of infrastructure projects are then to be sought by the individual SOEs who are engaged in their construction. If there is a ceremony that will involve diplomats and policymakers once a project is completed, then perhaps it will be an outcome listed by the MFA.

In this sense, the examination of the report on the outcomes of 16+1 helps us learn more about China’s role as a complex external actor in CESEE. To gain better knowledge about how China’s policymakers gauge their efforts and successes, it is worthwhile to compare this document with other similar documents, not only on CESEE, but also on other regions of the world. In practice, however, the publication of such report may not be necessarily perceived in the most welcoming ways by CESEE policymakers and researchers, because it lacks what they perceive as substantial – and that is economic data. Cynics may as well say that, in the absence of tangible outcomes, the MFA simply presented a list of meetings and documents. However, the list of outcomes that specifically emphasizes policy communication and measures, institution building, streamlining of development agendas and people-to-people exchanges, shows that for now, China’s approach has a different logic. For now, China seems to focus on setting the stage, creating a conducive climate, securing mutual trust, building guanxi, forming a community of CESEE “China insiders” and experimenting with policy frameworks, before significant economic cooperation takes place.

Anastas Vangeli is a Doctoral Researcher at the Graduate School for Social Research at the Polish Academy of Sciences and a Claussen-Simon PhD Fellow at the ZEIT-Stiftung Ebelin und Gerd Bucerius.

[1] I am grateful to Dragan Pavlićević of the Xi’an Jiaotong – Liverpool University for this observation

Download

Copyright © 2024. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved