On October 19th 2018, in the occasion of the 12th Asia-Europe meeting in Brussels, a Free Trade Agreement (EUSFTA) was signed between the European Union and Singapore, allegedly aimed at cutting tariffs, removing trade barriers and simplifying trade rules between the two parties. This document was complemented by an Investment Protection Agreement (EUSIPA) bound to replace 12 previous bilateral treaties between the two parties. With these proceedings, trade commissioners of both parties publicly conveyed their willingness to enhance businesses’ savings and safeguard consumer protection, social rights and environmental rules in the countries of the European Union as well as Singapore.

Singapore is the only ASEAN country to have signed a free trade agreement (FTA) with the EU[1]. Moreover, the current EUSFTA is unique in its form and scope. The agreement has been heralded as a stepping stone for the whole ASEAN region and for the role that the EU will play in it, both on an economic and foreign affairs level.

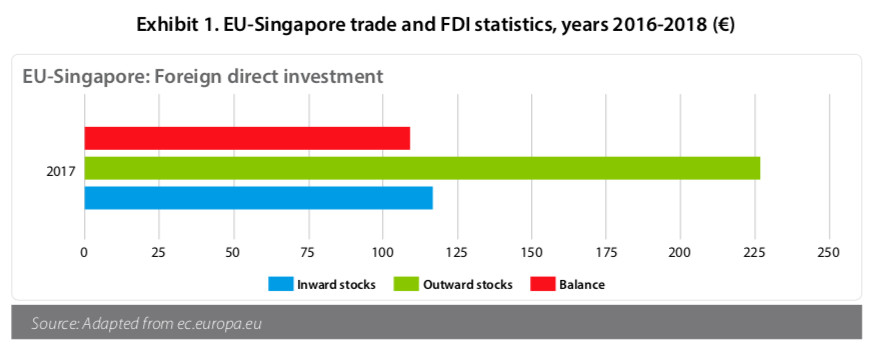

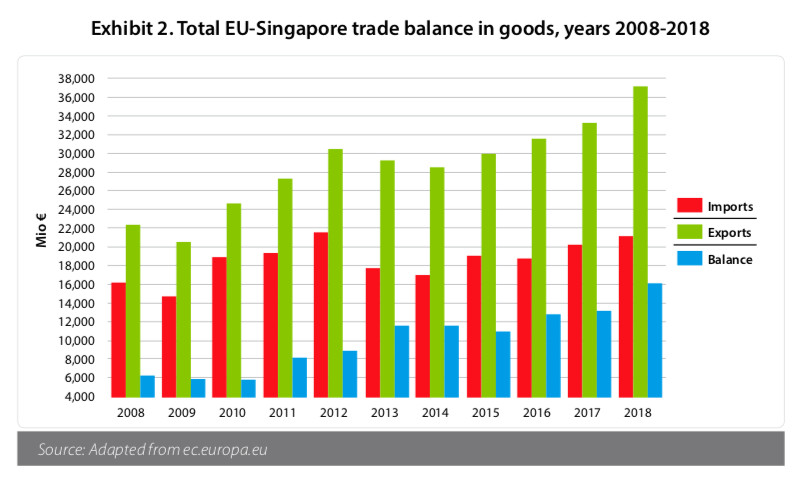

Singapore, with its 5.6 million individuals, is the EU’s largest trading partner in the ASEAN region, and its 14th largest trading partner globally. Total bilateral trade reached 58.1 billion € (in goods) in 2018 and 51.1 billion € (in services) in 2017 [2] (see Appendix), this latter figure having doubled since 2010 [3]. The EU is also the largest foreign investor by region in Singapore, with approximately 227.1 billion € of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in 2017, making it the 6th destination for outward FDI stocks3. Singapore, on the other hand is the 12th largest source of FDI stocks in Europe3, with approximately 117.3 billion € of FDI in 2017 (see Appendix).

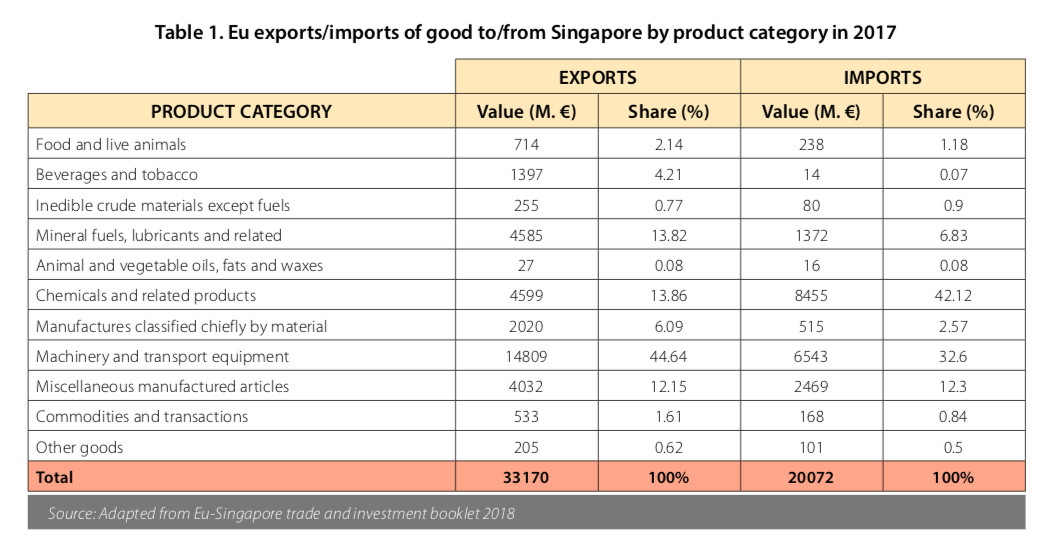

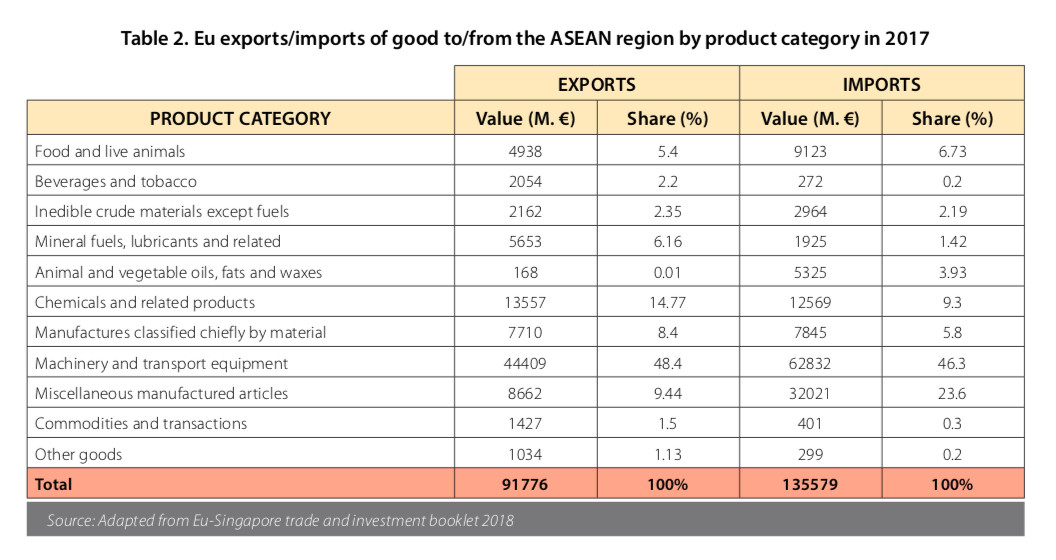

But the EUSFTA also entails a more expedited access to the broader ASEAN region, a market of 650 individuals with rising taste for western products. Indeed, a large portion of the more than 10000 European companies currently present in Singapore are exploiting it as a trading and connecting hub to operate more extensively in ASEAN (see the Appendix for more thorough imports-exports statistics by product category between the EU and Singapore as well as the ASEAN region as a whole). Concurrently, locally based firms have been also pronounced to benefit from an easier access into the EU. Channel News Asia and Tat Hui Food, for instance, are gearing up to foray with new ventures into the EU, and so is CapitaLand, which envisions to invest in European commercial real estate projects. Indeed, estimates from the Singapore’s Ministry of Trade and Industry maintain that the agreement will translate into a 1.1 yearly percent increase in total trade, and, consequently, in a 0.27 percent increase in annual GDP growth for the city state [4].

However, notwithstanding these optimist interpretations of policymakers and the press in general, and although trade commissioners of both parties, as well as Singapore Communications and Information Minister S. Iswaran have stressed the agreement’s economic benefit to small medium enterprises (SMEs) due to a greater degree of transparency and clarity of trade procedures, our research shows that several aspects of the agreement still remains unresolved, that several policy changes have been slow to be implemented and that overall clarity on the timing of regulations’ change is yet unclear. In view of this, in the following sections, an outline of the primary advantages that the agreement has been alleged to bring about for firms on both locations will be followed by an overview of the apparent incongruities between the purported aim of the agreement and the findings of our research. These incongruities will be made clear by using the example of the current state of affairs in trade policies in Singapore as perceived by trade practitioners locally, with particular focus on the Food and Beverage Industry (F&B).

Alleged advantages of the agreement to firms

The EUSFTA was announced to streamline several aspects of current EU-Singapore trading procedures, namely tariffs, non-tariff barriers, government procurement opportunities, and IP rights. A more detailed explanation of each aspect is as follows.

Removing tariffs

The deal aims to gradually remove all currently remaining tariffs on a wide array of products ranging from electronics to processed food, from pharmaceuticals to petrochemicals. For example, Asian processed foods made in Singapore, such asLap Cheong (Chinese dried sausage), fish balls Ikan Bilis (local anchovies), Roti Prata (local flatbread) are to benefit as they can be exported to the EU without tariffs up to a limited combined quota of 1250 tons per year. As for the timeline, Singapore will remove tariffs on 84% of all Singaporean products entering the EU, and the rest will be removed over a period between 3 to 5 years.

Non-tariff barriers

The deal aims to remove all remaining non-tariff barriers, e.g. by recognizing EU food trade standards, by removing duplicative conformity tests for electronic goods, by adhering to the recognition of international standards for vehicles parts, and by removing the inspection requirements of food processing plants for exporting companies. The deal is also purported to streamline the custom procedures and generally facilitate trade. Product inputs sourced by Singaporean businesses from other ASEAN Member States will be considered as domestic, i.e. originating from Singapore, and thus enjoy the agreement regulations.

Government procurement

The deal will make it easier for European companies to compete for government procurement contracts in Singapore, and vice versa, including railway services, IT services, telecommunication services, construction and infrastructures.

IP rights

Singapore meets its food requirements almost exclusively by importing. Today, Singapore has no duties for imports of agri-food, and this has been maintained in the agreement. More importantly, the deal establishes that the geographical indications (GIs)[5] valid in the EU will be also respected in Singapore, guaranteeing identity to wines, spirits, and certain agricultural products, thereby improving local consumers’ awareness of authenticity and quality of European products. 196 geographical indications originating from various parts of Europe will be respected and preserved in Singapore. These include meat products, cheeses, wines, spirits, beers, fruits, vegetables, cereals, oils and fats, breads and pastries, cakes and confectioneries, natural gums and raisins. GI registration procedures will be enforced in Singapore similarly to the EU, and these trademarks will be protected by enforcing registration rejections for non-GI compliant products using erroneous names. In other words, the deal establishes that products and services will be sold in Singapore under the same conditions they are currently sold within the EU.

Advantages to firms or lack of clarity on procedures?

Despite the advantages that the agreement has been announced to bring about to firms of both signing parties, our research shows that several aspects of its implementation appear either unresolved or unclear, and that the alleged benefits of the deal to SMEs is not yet clear.

The information that we report is based on numerous semi-structured interviews that we have conducted with practitioners who are currently operating in international trade between Singapore and at least one European country.

In the particular case of the F&B industry, for instance, it is still impossible to import cold cuts unless they are cooked, or meats unless aged above 100 days. Surprisingly, these products are sold without constraint within Members States of the EU. The trade agreement, which should be meant to imitate the intra-European trade policies, seems to not have been congruent with its purported aim as of spring 2019. Differences with regards to which nations within the EU are allowed to import certain products to Singapore seem also still present. Indeed, in one of our interviews, a Singapore based food and wine distributor active since 2000 has reported to us that meats can be currently imported form locations such as France, Scotland, and Ireland, but not from Italy. Recently, stricter policies on the nitrite and nitrate content of certain food categories have also rendered impossible to import to Singapore foods with components such as mushrooms, while this limitation is absent with regards to trade of the same foods within the EU. Alcoholic products are also still affected by a hefty custom duty (88 SG$ per litre of alcohol) levied on alcoholic beverages imported from foreign countries independently of the location of origin, which the agreement doesn’t seem to tackle despite its alleged role of trade conditions equalizer.

Furthermore, although the more sophisticated GI recognition system of the agreement is supposed to enhance various European F&B products reputation locally so that they can possibly command higher prices if compared to other products on the market, it has been noted to us that these products are still locally sold along with products of non-EU origins using European denominations, e.g. mixture of chesses named “Mozzarella” and produced in Australia.

In the case of the the automotive sector, the main obstacle to import vehicles is a tax on luxury items, of a minimum of 40%, levied in ascending levels and based on engine capacity, valid for both automobile and motorbikes. This tax is still in place and the trade agreement doesn’t seem to be aiming at reducing it.

Therefore, although the agreement has been announced to particularly benefit SMEs on both locations, the advantages that European SMEs can garner from this agreement, being these operating primarily in sectors such as the above, appears to be little.

Moreover, the effect of the agreement on the trade activities of more global giants are also questionable. The export activities that Singapore per se is primarily undertaking are majorly in three relatively high-end sectors: electronic chips, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals. It is unlikely that facilitation in custom procedures in this agreement will substantially affect, monetarily, the trade of these multinationals on a global level.

It seems that the advantages of the agreement are therefore likely circumscribed to local SMEs willing to venture into the European market rather than the other way around. In this regard, it will be possible to exploit the agreement’s allowance to source relatively cheaper raw materials from other ASEAN Member States while having them recognized as Singapore-made, and to possibly capitalize on new business opportunities in Europe such as the demand for niche Asian foods made in Singapore.

These minor advantages notwithstanding, the agreement has to be seen through a broader EU-ASEAN perspective, rather than through an EU-Singapore perspective. ASEAN is the fifth largest trading partner with the EU, with a total increase of trade in goods of 9.2% in 2017 from the previous year[6]. Singapore, being the largest trading partner with the EU among the ASEAN Member States, is a hub and bridge for global firms to do business in the broader ASEAN region. In this view, the agreement is a clear signal of trade cooperation between two influential blocs outside of the emerging China-USA trade asperity, an attempt to eschew siding with any of the two superpowers while pursuing beneficial transnational economic advantages. The broader political significance of the agreement become then clearer when one views this higher-level priority in comparison to the actual benefit firms are bound to garner from it. Interestingly, this is corroborated by a backdrop of a general lack of clarity regarding the tangible benefits of the agreement to the currently operating SMEs in the region. Ronne Wong, Chief Operating Officer of the Association of Electronic Industries in Singapore expressed the lack of understanding regarding the potential perks for local firms. Industry specific information also seems to be lacking at the moment. Singapore Fintech association president Chia Hock Lai said that his organization is literally waiting for more clarity on the agreement to determine how its member companies can capitalize from it. David Tan, the president of Singapore Food manufacturers Association, noted that the deal, being signed at a governmental level, would benefit from more substantial outreach efforts to other corporate level associations.

In our interviews, it has surfaced numerous times that the function of this trade agreement has to be viewed in a broader economic and political context, i.e. a diplomatic instrument to display a commitment to international economic cooperation. For Instance, Bruno Liotta, current Director of the Italian Chamber of Commerce in Singapore (ICCS), maintains that the document-level simplification announced by the agreement seems moot given the already smooth custom clearance processes in Singapore if compared not only to neighbor countries but also to international trade standards. Indeed, the custom procedure to apply for certificates of origin can currently be finalized online by filling up a form.

In conclusion, the benefit that SMEs can garner from the agreement are likely limited to local firms wishing to operate in Europe by exploiting regulations on sourcing and exports. The custom facilitations purported by the agreement are apparent primarily on paper, while the commitment of alignment in bureaucracies might not be a short-term priority in comparison to the higher-level policy agenda. These conclusions notwithstanding, we suggest European SMEs enterprises currently operating in Singapore or wishing to do so to closely monitor the development of the agreement implementation agenda. Indeed, it has to be noted that a partial cause of the current lack of clarity could be that some regulations of the deal will be gradually enforced over a 5 years time period. Should this be the case, however, we are also left waiting for a clear agenda delineating the policy and regulatory changes to convert trade agreement policies into commercial activity so that firms on both locations will be able to optimize their planning.

[1] Negotiations for a FTA between the EU and Vietnam, an ASEAN Member State, were concluded in December 2015, but the agreement has not t been signed yet as of spring 2019.

[2] http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/singapore/

[3] https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eu_singapore_trade_investment_2018_edition.pdf

[5]GI is a sign that uniquely distinguishes products originating from a particular location due to their high standard of quality or reputation. There are different kinds of GI, such as Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), i.e. products processed in a specific territory throughout all of the stages of their production; Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), i.e. products processed in a specific territory at least in one stage in their production; or GI for spirit and wines, which identifies alcoholic products originating from a specific location, such as. Cognac or Scotch, for instance.

[6]https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eu_singapore_trade_investment_2018_edition.pdf

Copyright © 2024. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved