Over the last decade we have witnessed a sharp increase in due diligence legislation for the minerals supply chain, codifying higher company performance requirements when it comes to the sourcing of gold. This is not the place to list all soft and mandatory legislation on supply chain due diligence; however, should the reader so desire they are welcome to take a look at this brief article by Camila Gómez Wills. For now, it is sufficient to note that civil society’s and customers’ expectations on responsible sourcing are progressively being embedded in law, as the European Union Conflict Minerals Regulation and the upcoming European mandatory human rights and environmental supply chain due diligence law demonstrate.

The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict- Affected and High-Risk Areas (henceforth, the OECD Guidance) adopted in 2011 by the OECD Council provides the framework used by legislators and companies in relation to responsible minerals sourcing. It has the objective of providing guidance on how to operationalize systems to ensure responsible mineral supply chains with a view to breaking the link between the production and trade of minerals and conflict financing, serious human rights abuses (the worst forms of child labour, forced labour, widespread sexual violence, torture, etc.) and white-collar crime (Annex II risks). The OECD Guidance underscores the crucial role of refiners in the gold supply chain in identifying, assessing and managing risks when sourcing from conflict-affected and high-risk areas (CAHRAs).

To help companies with their responsible sourcing obligations, the European Commission (EC) published a non-exhaustive and regularly updated list of CAHRAs – meaning a list that does not contain all the items that meet the criteria of the list. As of 11 February 2021, the list contains only a small number of examples of CAHRAs, the threshold for which, in our opinion, is met in many but not all countries with sizeable artisanal and small-scale mining populations. Companies should use this list to inform understanding of the risk profiles of countries and areas requiring deeper due diligence. In no way does it serve as a sanctions list or a list of places that should not be sourced from. This is a misconception, and one that it is important to counter – because disengaging with CAHRAs only fosters illicit trade, which is a fertile breeding ground for Annex II risks. Unfortunately, misconceptions in industry are hard to dislodge. Take the example of Section 1502 of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. More than a decade after it was passed, several refiners’ employees still believe that this law prohibits sourcing from the Democratic Republic of Congo and bordering countries. In fact, these legal requirements encourage responsible sourcing, which is a precondition for cleaning up global supply chains.

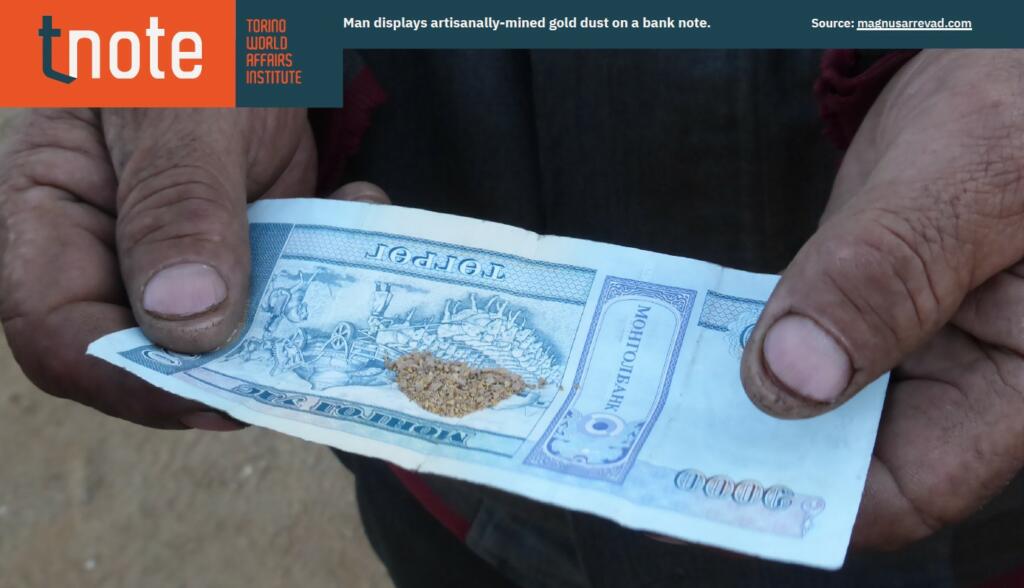

Man displays artisanally-mined gold dust on a bank note. Source: magnusarrevad.com

Nevertheless, some gold refiners still decide to stop sourcing gold from CAHRAs in order to de-risk their supply chains and avoid the possibility of sourcing smuggled gold or gold that contributes to human rights violations and conflict (see, for instance, the case of Metalor). This may be the easy option, but it is not the responsible option. In such instances, refiners tacitly accept the status quo, thereby failing to actively contribute to reducing the unregulated space in which illegal and criminal networks thrive. According to the OECD, disengagement and de-risking should be an option of last resort. It recommends that refiners work to identify and mitigate risks in mineral supply chains, where it is possible to do so. This relationship should then actively contribute to the continuous improvement of supply chain performance, which is after all the name of the game. And yet, many refiners still find this recommendation challenging and difficult to implement. Tackling complex supply chains and high-risk countries can be a daunting task for refiners, especially small- and medium-scale entities. Avoiding sourcing from these areas may therefore feel like the safest bet, especially when the commercial and reputational risks are high; this approach is understandable but not advisable for the reasons outlined above.

So, given the risk-averse attitude of many refiners, how can they best champion responsible sourcing and actively contribute to positive impact by providing an alternative to the illegal exploitation of gold? We propose two ways, which are not yet widely adopted:

To summarize, continuous improvement through engagement is essential if we are going to scale up the responsible sourcing of gold, and we should all support those members of the industry that are prepared to be front runners in navigating the inevitable challenges.

Authors

Fabiana Di Lorenzo is the Senior Manager of Responsible Sourcing at Levin Sources.

Adam Rolfe is Senior Manager of Good Governance at Levin Sources.

This T.note has been updated on 15-04-2021.

Download

Copyright © 2024. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved