2020 was undoubtedly a year of significant changes and transformations, which the healthcare and economic crises faced by the majority of countries worldwide accelerated. One case worth deeper observation is represented by the Kingdom of Thailand, which has been ranked sixth among a total of 195 countries in terms of health security. Thailand is also ranked number one in Asia for health security (followed by South Korea) and is the only developing country in the world’s top ten.

Given the Kingdom’s relative success in handling the pandemic, one may wonder why it was so politically turbulent in 2020, with several protests staged in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area (BMA), as well as across the country. Thailand, formerly Siam, is known for political instability, since a number of coups d’état have happened over the last century. However, after the general elections of 2019, with the victory of a coalition led by the newly formed, military-friendly Palang Pracharath Party, the political situation appeared to be one of solidification of the position of the incumbent parties. What changed this course of events?

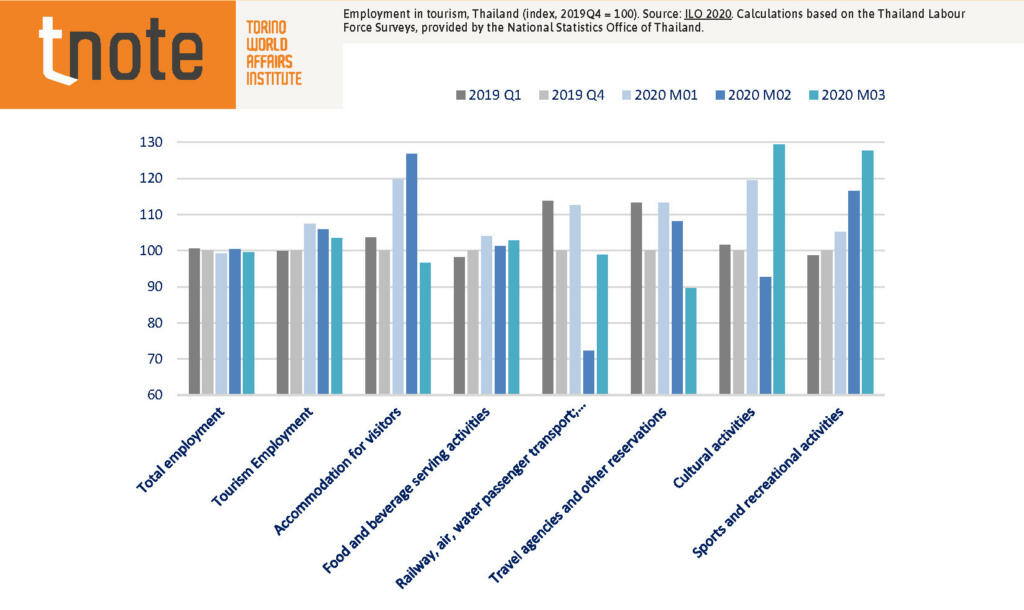

First of all, the impact of the coronavirus pandemic has been staggering. The Federation of Thai Industries has estimated job losses at a record two and a half to three million in 2020 alone, of which more than a million are in the tourist sector. Thailand has a workforce of about thirty-eight million. The impact is devastating also in terms of economic losses, as Thailand relies more on tourism than any of its neighbours – tourism (both international and domestic) makes up 21.6% of Thailand’s GDP, compared to Cambodia’s 6.7% and Vietnam’s 6.9%. Almost a fifth of Thai GDP has been wiped out by the current economic crisis.

This economic calamity hit an economy that was already troubled by a decrease in exported merchandise, whose gross value in 2019 was $246.244 billion dollars, showing a 2.7% decline from 2018, due to the geopolitical tensions caused by the more assertive US trade policy towards China.

From a domestic perspective, the Thai economy has shown some worrying signals too. As of June 2020, household debt rose to THB 13.6 trillion, equal to 83.8% of GDP, the highest since 2003 and among the highest levels in Asia. Household debt had stood at 79.9% of GDP at the end of 2019. This dramatic increase has prompted the Bank of Thailand to warn that ‘household debt levels, already at the highest in 17 years, are expected to rise further, as the coronavirus pandemic hammers Thai trade-and tourism-reliant economy’.

In fact, political struggles began in the second quarter of 2020 within the parties of the majority coalition, who challenged the economic direction taken by the previous technocratic and military-sponsored cabinet (which seized power in 2014). Some of the most prominent members of the previous government – namely, the PM, Prayut Chan-o-Cha, the Defence Minister, Prawit Wongsuwan, and Dr Somkid Jatusripitak – also served in the new cabinet formed after the 2019 general elections. In mid-2020, the Palang Pracharath Party sought to reduce the influence of the Deputy PM, Dr Somkid Jatusripitak, and his economic team, composed of the Finance Minister, Uttama Savanayana, the Energy Minister, Sontirat Sontijirawong, and the Minister of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation, Suvit Maesincee. All of them resigned on 16 July 2020.

Notably, Dr Somkid was the mastermind behind the Thailand 4.0 digital masterplan enacted in 2014, whose targeted industries included advanced automotive and auto parts, electric vehicles, smart electronics, affluent medical tourism, smart agriculture and biotechnology, robotics for industry, aerospace, and biofuels and biochemicals. On 5 October 2020, after a long-running vacancy, Arkhom Termpittayapaisith, former Minister of Transport, was royally endorsed as the new Finance Minister.

Since mid-2020, Thai citizens (particularly urban youth, including high-schoolers) have been taking to the streets to protest against the policies of the government and call for constitutional reforms of the Kingdom – the current Constitution was enacted in 2017, after a referendum, and under it Thailand adopted a democratic regime of government with the King as the head of state; the first Constitution of the Kingdom was issued in 1932, to end the absolute power of the monarchy. Demonstrators have adopted tech-savvy and social-media-enabled tactics to form mobs at multiple junctions in Bangkok, to avoid confrontations with the authorities.

In a pandemic emergency situation, politics and economics are usually strictly related. In these protests, economic factors have certainly played an important role, which becomes especially clear when we look at the actual outlook for Thai urban youth. All major indicators show that youth unemployment is posing a historic threat to the development of the Thai economy. The Bank of Thailand has predicted that the unemployment rate will increase eight to twelve times year on year (either way, the highest in the past twenty years), with the most vulnerable group being Thai youth, especially fresh graduates.

Further, the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council has announced that the pandemic may result in a youth unemployment rate of over 5%, which is five times higher than the average adult unemployment rate in 2019 (1%). This is still an optimistic projection: based on data by the National Statistics Office of Thailand, youth unemployment already reached 10% in 2020. The shortage of jobs that has accompanied the recession has also put fresh graduates at high risk of unemployment in 2021, when around 500,000 new graduates will flow into a stagnant job market.

Although youth unemployment is concerning and all forecasts are grim, Thailand can still rely on strong economic foundations, which make its economy resilient to downturns and external shocks. For instance, the public debt ratio of the Kingdom stands currently at 48%, and despite significant stimulus measures in response to the pandemic, it should not rise beyond 57% (the legal threshold is 60%) over the next five years, with the government continuing to incur a budget deficit at an average of 2.8%–2.9% of GDP.

Everyone in Thailand has a stake in mitigating the risks to the long-term stability of the country and in grasping the opportunities presented by the interest in Southeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific by all major international actors, including China, Japan, the US and Europe. A pivotal role will be played by the Thai higher education industry, which is now called on to make a major contribution to the upskilling of the current and future workforce, to transform the Thai economy into an authentic ‘digital’ and ‘smart’ nation through increased labour productivity and enhanced entrepreneurship and innovation-related skills.

Author

Pietro Borsano is Deputy Director (Industrial and Global Alliances) and senior lecturer at the Chulalongkorn School of Integrated Innovation.

Download

Corso Valdocco 2, 10122 Torino, Italy

Sede legale: Galleria S. Federico 16, 10121 Torino

Copyright © 2025. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved