Introduction

On 1 February 2021, Myanmar experienced the third coup d’état in its history. This coup surprised even the most seasoned Burma watchers, who, as a result, have tried to formulate coherent explanations, give assessments of the current situation, or provide possible scenarios for the future. At the time of this writing, it is still difficult to grasp how this return to authoritarianism will put an end to the country’s post-2011 opening to the external world and the associated decade of (mostly incomplete) economic and social reforms. To contribute to this scholarly debate regarding what was happening within this complex stage of the political life of the country, especially in terms of collective participation in the process of political and social change, our work focuses on a specific policy sector: higher education. In so doing, we answer the following questions: What is the new mission of higher education within the State Administration Council’s (SAC) state project? What is the impact of the SAC’s actions at the institutional level (i.e., in everyday life) in university spaces? Who are those who contest the vision of higher education that the state authority is imposing? And what is the idea of higher education that these opposition groups are proposing?

From a methodological perspective, this study is based on qualitative data collected through semi-structured interviews with governmental officials and university teaching staff. Our interactions were exclusively virtual. Despite the limitations of conducting ‘online fieldwork’ through Zoom calls, we were able to collect relevant information and get an idea of the perceptions, emotions, choices, and, ultimately, strategic decisions of the actors involved in the higher education sectors. Our “positionality” as foreign researchers with solid connections to Myanmar universities and civil society organizations and individuals helped us access higher education actors quite smoothly and establish the necessary interviewer–interviewee trust. Simultaneously, this positionality required us to be very aware of potential personal biases when interpreting data. To bolster the interpretations offered by our interviews, we triangulated their accounts with additional sources, including movement documents – mostly social media material – and journalistic or international agency reports.

After highlighting a few conceptual frameworks on the politics of higher education, the article reviews how the military juntas have shaped higher education from a historical perspective (1962–2011), the reform of higher education during the transitional period (2011–2021), and the coup’s impact on the sector. The article gives specific examples of how the SAC is moving forward with a national vision on higher education by replicating old Tatmadaw policies and strategies and agrees with Khaing Phyu Htut, Marie Lall, and Camille Kandiko Howson that the Tatmadaw seems to believe the old procedures can be successfully reapplied (Htut, Lall, and Howson 2022). These policies are not only halting the ongoing crucial higher education reform but also creating new institutional conflicts. At the same time, on the other side of the divide, actors in the social movements are re-imagining a new higher education system. They are framing new visions for universities deeply rooted in the idea of an education suited to a federal and just society. These frames are even more transformative than the ones at the core of the recent higher education reforms. The conclusion highlights a few analytical points on the dynamics of the new state authority’s un-making of higher education and the re-invention of educational spaces created by resistance movements in post-coup Myanmar.

Higher education: State authority and the social movement nexus

A higher education system is built to teach, conduct research, and carry out service activities for the wider society. These functions are often interrelated, but not all of them have equal priority in every institution or society; in some cases, one or more may be missing completely (Altbach 2009; Bourner 2008). In carrying out these functions, higher education institutions play important social, political, economic, and cultural roles in societies (Brennan, King, and Lebeau 2004; World Bank 2000). These roles have been portrayed in different ways in the prevailing educational discourse. Higher education can support economic and social development by fostering the production of human capital and the growth of a knowledge society; it can perpetuate, legitimize, and reinforce the position of dominant elites in society; or it can be a force for progressive social change and for creating a more “just society” (Moore 2004). Ultimately, each higher education system impacts (or not) the society in which it is embedded in different ways according to the mission and vision it pursues. This “ambiguity” makes higher education both an interesting and a complex field of analysis. Higher education is an interesting field because the unpacking of the political tensions that play out in its spaces can shed light on various features of the political system and society in which it is embedded (as our work ultimately aims to do). At the same time, the fact that each system is different makes this unpacking quite complex. Geographical, historical, and cultural contexts play an important role.

In seeking to understand the contemporary role of higher education, a central premise is that, in many nations, universities are created, chartered, financed, and governed by the state: This means the state is intertwined with and – in some political systems – inseparable from higher education. Acknowledging the role of government, as well as other institutions (i.e., the legal and executive branches of the state, regulatory entities, and institutions of national security), state-theoretical models have offered a holistic approach to studying the politics of higher education. Brian Pusser (2018) notes that the first question to be asked of the state and higher education in any given national context is: “What is the mission of higher education within the state project, and what role do various elements of the state play in meeting that mission?” In other words, in most national contexts, the purposes of a public political institution such as a university can be ascertained by paying attention to the state and the role of a particular institution in the state project. State missions influence educational policies. At the same time, universities are independent agencies with core missions and characteristics: They are not always easily directed and not always responsive to the will of political authorities. Using Pierre Bourdieu’s terminology, higher education can be considered a “field,” a space in which various actors interact: “constant, permanent relationship of inequality operate inside this space, which at the same time becomes a space in which various actors struggle for the transformation or preservation of the field. All the individuals in this universe bring to the competition all the relevant power at their disposal. It is this power that defines their position in the field and, as a result, their strategies” (Bourdieu 1998).

Universities find themselves at the nexus of powerful tensions created by different actors involved in this field. Among these actors, there are the disenfranchised, excluded individuals and groups that arise as social movements to influence the power structure, institutions, or both. It has been conceptualized that social movements and universities go hand in hand (Pusser 2018). As sites of critical inquiry and symbols of national purposes, universities have often been central to the mobilization of various social movements (student movements taking center stage) aimed at drawing attention to demands for change, influencing the state, or pressuring civil society to take action (Pusser). Referencing the long history of conflicts in universities’ spaces between authorities and elements of the civil society, Ordorika and Lloyd frame each education reform as “a historical product of power struggles between dominant and subaltern groups in education and the broader state; explaining the dynamics of educational reform as a consequence of competing demands for the reproduction and production of ideology and skills on the one hand and struggles for social transformation and equality on the other; and establishing the linkages between political contest at the internal and external levels as central to understanding new sites of educational contest and reform” (Ordorika and Lloyd 2015).

Along these lines, in the following section, we highlight the interplay between state authority and the actions of social movements in shaping higher education in the modern history of Myanmar – specifically, between 1962 and 2011. This historical perspective shows the complexity and ambiguity of how Myanmar’s universities are both fields of contestation over state authority and legitimacy and instruments in broader contests for control over the state.

The history of higher education in Myanmar under military juntas

The Myanmar higher education system was built by the British colonial powers to educate a very small segment of the urban population and generate the skilled workforce required by the colonial administration. Throughout colonial times, university students represented a small (less than 1,000 individuals) elite in a country where only two cities had universities (Yangon and Mandalay), and the subjects that were taught mostly related to law, arts and sciences, medicine, and engineering (Hellmann-Rajanayagam 2020). At the same time, university students became one of the most significant collective actors of that time. In the 1920s and 1930s, the campus of the University of Yangon was a laboratory for the formulation of radical nationalism that, extending outward past the spaces of elitist higher education, shaped the country’s political trajectory. During World War II, the same student leaders began to leave their university studies to organize the armed struggle for independence and establish their place in the “political mythology” of the country, which still allows student organizations to play their long-lasting role as contentious political actors (Altbach 1989).

Since gaining independence in 1948, Myanmar has routinely been ruled by military juntas. During the Ne Win era (1962–1988, including the periods of the Revolutionary Council and the Burma Socialist Program Party), higher education transformed amid waves of reform. These educational reforms were carried out within a broader political and economic context and were inextricably linked to the project of building a modern socialist nation in keeping with the Burmese Way to Socialism policy framework. Higher education was subservient to the technological needs of a socialist country and was maintained under strict state control, which led to the nationalization and centralization of all activities. Higher education institutions were to emphasize the type of knowledge and expertise required by the socialist economy and industry. For instance, medicine, statistics, and education were considered “non-economically linked or non-industry and non-economy linked studies,” whereas technological subjects, agricultural sciences, and veterinary sciences were labeled “economy- or industry-based studies” (Zarni 1998). Through eloquent rhetoric of inclusiveness and social justice, higher education was made into a field largely closed to the intervention of both student politics and international actors who might potentially lead to contestation and resistance. Meanwhile, military education was portrayed and valorized as the best possible education, one that – unlike the other higher education institutions – could provide secure social and economic status. General Ne Win’s policies led to a total crackdown on higher education during the regimes of the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) and later the State Peace and Development Council, a period in which higher education was spatially and administratively fragmented and cognitively separated from wider society.

After 1988, all universities were closed for three years (until May 1991), and gatherings of more than six people became illegal in the country (Sheader 2018). During this three-year closure, the SLORC initiated a systematic purge of civil servants, including teachers and university lecturers. When they were reopened , universities and colleges by default became the only places other than monasteries where large groups of people could gather, the regime having shut down all other potential forces of opposition (Koon-Hong 2014). At any sign of protest (the main protests of the 1990s took place in 1992 and 1996), the regime stepped in to interrupt academic activities: In Yangon, between 1988 and 2000, the universities were closed for 10 out of the 12 years (Lall 2008). After 1996, both Rangoon and Mandalay universities were prohibited from enrolling undergraduate students, a situation that was not reversed until 2015. During the extended period of closure, university and college teaching staff were often asked to attend “retraining camps.” Rives describes a four-week “re-education” course at the Phaunggyi Central Institute of Civil Service (about 50 miles north of Rangoon) that Rangoon University staff were obliged to attend in early January 1992, about a month after the student demonstration celebrating Aung San Suu Kyi’s Nobel Peace Prize award that led to the shutting of the campus (Rives 2014). The camp was run by the military, and it included instructions and lectures on national unity and patriotism and how to enforce student regulations in practical terms. The ultimate goal was to indoctrinate, re-educate, and control the university staff. Practical advice about monitoring students included surveillance in halls and bathrooms; on some campuses, a military system of control was implemented in which corridors and staircases were divided into security units under the command of department heads.

The military junta progressively split and relocated existing higher education institutions and established new ones (mostly lacking student dormitories) in remote locations far from urban centers. Students and staff from the existing higher education institutions (around 32 at the end of the Ne Win era) were transferred to 156 newly built institutions or campuses outside the main urban centers (Shah and Lopes Cardozo 2018). These institutions had a smaller number of students, which prevented the formation of student groups capable of organizing contentious actions. The different universities were divided among 13 line ministries, placing the medical universities under the Ministry of Health, for instance, and leaving only the non-technical arts and sciences universities under the Ministry of Education. Not only were the new institutions built in unsuitable locations, but they were also built in a hurry with poor materials; teaching spaces were not carefully planned, laboratories remained under-resourced, and libraries stocked materials that were obsolete and outdated. The teaching, learning, and research in universities were all profoundly affected. Curricula were reduced to narrow texts, critical thinking was removed from the learning process, and rote learning became the main pedagogical approach, a situation that continues to this day (Po Po Thaung Win 2015). Access to the country’s universities was highly restricted, with admission often given out as a reward for political loyalty and compliance, and large numbers of students were channeled into the vast new distance education system (Lorch 2007). Distance education was not only more economically accessible (lower fees), but it also continued to operate during periods when regular universities and colleges were closed without any clear schedule for reopening (from the authors’ interview with a Ministry of Education official in 2020). The official narrative focused on using information technology and multimedia facilities to offer better education to the masses; most scholars note that, in reality, the Tatmadaw was determined to prevent any further disruptions caused by uncontrolled gatherings of students.

The result was a higher education system in disarray, which was still the case when the 2011 political transition began. In a speech at a Myanmar–UK higher education policy dialogue event convened by the British Council in 2013, Aung San Suu Kyi (leader of the opposition at the time) noted that “the standard of our university education has fallen so low that graduates have nothing except a photograph of their graduation ceremony to show for the years they spent at university” (Mackenzie 2013). This condition is widely acknowledged in Myanmar. The country’s higher education system is poor by global standards (CESR Team 2014; 2013). In the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index for 2015–16, Myanmar’s higher education and training was ranked 138 out of 140 countries (Schwab 2015). These shortcomings span multiple areas: the physical and digital infrastructures are inadequate; the system’s human resource capacity is poor by any standard; teachers are given few opportunities and little incentive for professional development; the teaching activities and curricula of most university courses are outdated and not well aligned to the needs of the country (Thein Lwin 2007); and, finally, research activities are limited (CHINLONE 2018). Moreover, the higher education system reflects the considerable inequalities running across Myanmar society. Youth from poor households are highly underrepresented, and the cost of tuition fees, study guides, boarding costs, and other auxiliary expenses constitute a significant barrier to higher education. Although only limited data is available, multiple scholars point out that several ethnic groups are underrepresented in the country’s universities.

Against this backdrop, a higher education system in which (military) government involvement in the daily affairs of universities was the norm for decades led to a system in complete disarray. Student organizations proved remarkably resilient during these periods, but the firm grip of the state prevented their actions from having a positive impact on the education system. In the next section, we turn to how higher education was reformed during Myanmar’s period of transition.

The 2011–2021 Myanmar higher education reform

From the onset of his presidency, President Thein Sein highlighted education as a space for reform that required the intervention of a large number of stakeholders (both local and international). Reversing the vision of Myanmar state authority for the first time since the 1960s, he asserted the success of the higher education system as a key element in the long-term drive to move the country forward, regain the respect of the international community, and establish a credible place in the ASEAN region. This new collective participation in educational matters took form in the “Comprehensive Education Sector Review” (CESR) process, an arena in which local and international actors could work together toward this goal. CESR quickly became dominated by the various aid agencies that were sending in experts and policy suggestions for influencing the reform process. In the same year, the CESR announced that an umbrella organization called the National Network for Education Reform (NNER) would be created. Initially, the NNER included the student organizations of the country, among others. It was intended as a political participation process aimed at making recommendations to Parliament to potentially inform the CESR. Thus, at the beginning, the NNER was firm in its intent to cooperate with government initiatives. Within a few months, however, it withdrew from this collaboration because the government-led reform process did not value or incorporate the public input (Metro 2016). Student organizations’ level of disenchantment and dissatisfaction grew with each step of the reform process, which led to a nationwide mobilization from September 2014 until March 2015.

Finding that the CESR process was taking too long and wanting to secure a set of education laws well ahead of the 2015 elections, the President’s Office initiated a parallel process called the Education Promotion Implementation Committee (EPIC) to draft policies for the implementation of educational reform. As a result of the work EPIC undertook, Parliament approved a new National Education Law (NEL) in 2014, which was amended in 2015. In late 2015, a brand-new five-year National Education Strategic Plan – 2016/2021 (NESP) was launched. Considering the premises of the NLD’s 2015 and 2020 election campaigns, Aung San Suu Kyi and her NLD party might well have been expected to play a decisive role in reforming higher education (Lall 2021). The reality was very different, however: not only did the NLD function less as a genuine opposition party and more as a bystander during the drafting of the NEL, but the trajectory of the education reform did not take any significant turn during the entire term of the NLD. Ultimately, the NESP drafted under Thein Sein’s presidency was only slightly revised, and the main aim in terms of higher education reform was to pursue better governance through autonomy.

The NEL and the subsequent amendment aimed to provide a national framework for the implementation of a range of complementary reforms across the national education system, such as a recognition of the right of all citizens to free, mandatory education at the primary level; the establishment of a standards-based education quality assurance system (thanks to the establishment of ad hoc commissions for quality assurance); an extension of the basic education system up to the age of 13; support for instruction in minority groups’ languages and cultures; and a greater decentralization of the education system. With regard to the higher education system, the NESP had three specific strategies: 1) to strengthen higher education governance and management capacity; 2) to encourage local teaching staff to undertake quality research and offer effective teaching, to provide students with an effective learning experience; and 3) to improve access to high-quality education without discrimination and regardless of students’ social and economic backgrounds. The NEL and the NESP put the issues of governance and management at the heart of the reform in the hope that changing the governance system would lead to better-quality education. In other words, higher education reform took the form of a quest to make a few carefully chosen and trusted universities autonomous from day-to-day governmental interference.

It must be acknowledged that the route to increased autonomy is a long-term process, and its effects are not always immediately perceptible at a macro-level, especially at the time of writing, shortly after the 2021 coup had interrupted the process before it could be completed. In an effort to map the specific stages and impacts of the overall reform process, a few studies have collected perceptions at the institutional meso-level (see, for example, Fiori and Proserpio 2021). These studies have found that higher education actors considered the ongoing reform beneficial in terms of enhancing the efficiency of higher education institutions (by linking decisions more closely to actions), improving the quality and relevance of academic programs (by allowing several universities to modernize and differentiate their degrees and courses), strengthening the relevance of teaching activities (by allowing higher education institutions staff to choose their academic paths more freely), and facilitating international relations with international partners. At the same time, issues of equity and access were not dealt with as top priorities, and there was very little progress on making universities more accessible to students from different social and ethnic backgrounds.

Lastly, it is important to mention how, throughout the entire “period of transition,” student organizations embraced a progressive idea of higher education and pushed for more “just” higher education with the potential to improve society (Proserpio 2022). Student organizations kept engaging in micro-level episodes of contention. These contentious activities mostly focused on endogenous educational issues and improving the well-being of students on campus without linking their claims to broader national political demands. The student unions repeatedly pointed out that higher education reform was at a standstill under the NLD government, and that the administration was unwilling to move forward with implementing decisions that had formally been taken on key matters. The key demands often raised concerned university autonomy and the drafting of institutional charters to legislate such autonomy; new regulations on the hiring and dismissal of university staff; an increase of the education governmental budget; the formal legalization of student unions that were active without proper legislation; and general freedom of expression and protest for students.

The SAC’s unmaking of higher education reform

When the coup happened, Myanmar’s universities were already de facto closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The SAC kept higher education institutions closed throughout 2021 and 2022, only allowing students in their final classes to take examinations, thus ensuring that students do not remain in the system for too long and could potentially create problems. In an online interview in December 2021 with the authors, the Ministry of Education’s officials asserted there are a few restricted pathways still open to enrolling students: some universities focused on medicine and computer science had been authorized to carry out autonomous selection processes, and a few universities closely tied to neighboring countries helped students find alternative routes for enrollment (e.g., the Mandalay Institute of Information Technology has an agreement with the Indian government and is encouraging students to apply to go study in India). Meanwhile, higher education institutions are by and large closed to most of the student population given that the SAC is changing the higher education field by shrinking the spaces of autonomy that were created during the period of transition.

As already mentioned, in the period of transition universities were gaining autonomy from both the organizational and decisional (meaning the university’s ability to decide on various academic issues) perspectives; staffing and financial autonomy, which are the other self-sufficiency sectors in global academia, were not really tackled. The SAC’s first actions were targeted at undermining these recent policies by bringing back the old policies and education structure that had been changed during the transitional period. As is made clear in the next section, these actions are coupled with (re)creating a climate of political violence, fear, and vulnerability that is (re)becoming a way of life in Myanmar academia, where teaching staff and students report being targeted with oppression and scrutiny (Moon 2022).

With regard to organizational autonomy, higher education institutions have been re-separated into different line ministries. In June 2021, the new Ministry of Science and Technology was put in charge of technical (33) and computer science universities (27) (a total of 60 institutions are under the umbrella of this new ministry), while the Ministry of Education is still in charge of the 49 arts and sciences universities, plus an additional 25 institutions (a total of 74 institutions are under the Ministry of Education). This “new” higher education organization is the “old” structure that had been in place before the recent reforms. The National Education Policy Commission (NEPC) has been abolished, and the NCC (National Curricula Committee) has been established as the sole coordination body, its main duty being to supervise university curricula. The NEPC was created as a new policy body by the NESP. The NEPC was a committee independent of the Ministry of Education mandated with formulating and implementing education policy reform, while the Ministry of Education retained only administrative duties. The NEPC was designed to play an executive role in advising and coordinating higher education policy and legislation in the form of Myanmar’s 30-year Long-term Education Development Plan, as well as coordinating with development partners, a role that had previously been assigned to the Ministry of Education. The abolishment of the NEPC could be seen as a step backward from the progress made in the past decade in terms of universities’ autonomy from state authority.

Concerning academic autonomy, the SAC is determined to take a firm grip of the curricula content once more, as is made clear by the NCC (National Curricula Committee) being the only coordination body. For decades under the previous military juntas, the university curricula had not only been inadequate compared with global standards but also disseminated Buddhist-Burman supremacy in a multi-ethnic society. One of the most evident achievements of the recent reform was the relative academic freedom that was granted by letting university staff set the teaching agendas (Fiori and Proserpio 2021). The same professors who had been so enthusiastic about the change are now concerned about their future teaching activities. The interviewed professors who have decided to maintain their position in academia even under the military junta have declared to the authors that they perceive increased scrutiny in their activities. This leads them to be very cautious not only in their classroom activities but also in the conversations they have with students and colleagues. According to our formal and informal discussions, the space for critical thinking and freedom of expression inside the university spaces is shrinking dramatically.

Lastly, government officials assert that: “the Roadmap of the new NESP 2021–2030 is still there. Nothing has changed for 2021–2030. The education policies are not so much changed at the moment” (from an interview with the authors, December 2021). At the same time, however, no real action is underway to implement any NESP policies; rather, all the efforts of state authority seem to be concentrated once again on fragmenting the higher education system.

New conflicts in higher education spaces

Higher education staff have taken a strong stand against the actions of the Tatmadaw and the SAC. Multiple sources point out that between 35% and 50% of the country’s teachers have abandoned their duties and given up their jobs to take part in the CDM.[1] In our virtual fieldwork, we collected the narratives of academics who have decided to join the CDM and the ones that kept their positions.

Among the CDM academics, we found three similar perceptions. First, “the Tatmadaw cannot be trusted when comes to education; this is a proven fact in the history of our country.” An SAC-run education system is not credible in the eyes of most university staff. Second, the higher education reform was opening up welcome spaces for debate and autonomy that academics are not willing to lose: “the progress was slow, but it was there, [and] now it is all lost… the Tatmadaw will recreate the old ways, an outdated system.” Losing one’s job as a university professor comes at great personal cost, especially since 80% of the staff is female. Even if an academic position is not well-paid, it comes with financial security that is hard for women in Myanmar to acquire in other ways. A former department head in one of the most prestigious universities in Yangon stated in an online interview:

My university was providing me a house in Yangon, but now I don’t have a salary, and I don’t have a house. I’m not married. It will be very hard for me in the future to make a living, but I couldn’t bear teaching under the military. Not after the past 10 years of progress and the activities that we have had, including international projects.

This last consideration brings us to the third common point that surfaced in the narratives we collected: the shared fear that the SAC will once again isolate the country from the outside world, starting with cutting all academic ties with international partners. Ultimately, the university staff that joined the CDM believed that losing their jobs was the only way to fight for a functioning higher education system since the SAC will have no interest in keeping the university running or providing quality education based on critical thinking, autonomy, and international engagement. According to our interviews, the punishment for a civil servant to join the CDM could vary according to not only the actions carried out by the single person but also their rank: higher-ranking civil servants (like heads of departments or pro-rectors) face more severe charges under Section 505(a).

In December 2021, we interviewed at length a professor based in Mandalay who decided to keep her position. She framed her reasoning in the following way:

I’m a teacher. If I don’t go back to the university, what can we do? If we make the revolution, we might win or lose. I’m a teacher; if the students come to the university, I have to teach. I teach only my subjects, not politics.

I have to do research for the new generation. That’s why I decided to return to the university and handle my department. At the time, two professors had left, and everything was locked. Then I took control of the department because otherwise other people would come and try. I work for my students and my subject, not for them. The students will come back one day.

I’m not a politician, but I understand what is fair and what is unfair, only that. I have to work for the university, the students, and the subject. I have to work for this community only, for the country, not for the government.

A conflict has arisen between CMD staff and those who have decided to stay in their positions. It is a conflict based on different perceptions of what constitutes the most honorable and suitable thing to do for Myanmar’s future and the current students. Regardless of the outcomes of the struggles in the coming months, it is evident that the bond and relationship of trust between and among students, teachers, and families has been broken.

Re-thinking higher education: The push toward federal education

At the time of this writing, the mass mobilization against the SAC, against all odds, has already continued for more than a year and is bringing new regional alliances and repertoires of contention into the national debate thanks, in part, to the support of other regional social movements, the so-called “Milk Tea Alliance.”[2] Student unions were part of the resistance movement since the early days, and their involvement remains active and constant. The SAC has promptly reacted by enacting old strategies: by abolishing student unions at universities and colleges throughout the country and supporting alternative groups known as student associations. Student union members believe the associations are supported by the SAC, the junta’s governing body, as part of an intentional strategy to undermine resistance to military rule (Frontier Myanmar 2022). Without fully analyzing the actors, grievances, and actions of this mobilization (which probably represents the country’s first transnational cultural revolution) here, we offer a few examples of what this mobilization is planning in relation to higher education, to support the argument that these “protests have accomplished what has been elusive to prior generations of anti-regime movements and uprisings. They have severed the Bamar Buddhist nationalist narrative that has gripped state society relations and the military’s ideological control over the political landscape, substituting for it an inclusive democratic ideology” (Jordt, Than, and Lin 2021).

Knowing that “we have nothing to lose but our chains,” one of the Marxist expressions popularized by groups such as the University of Yangon Student Union, student organizations are boycotting and fighting the current SAC control of education.

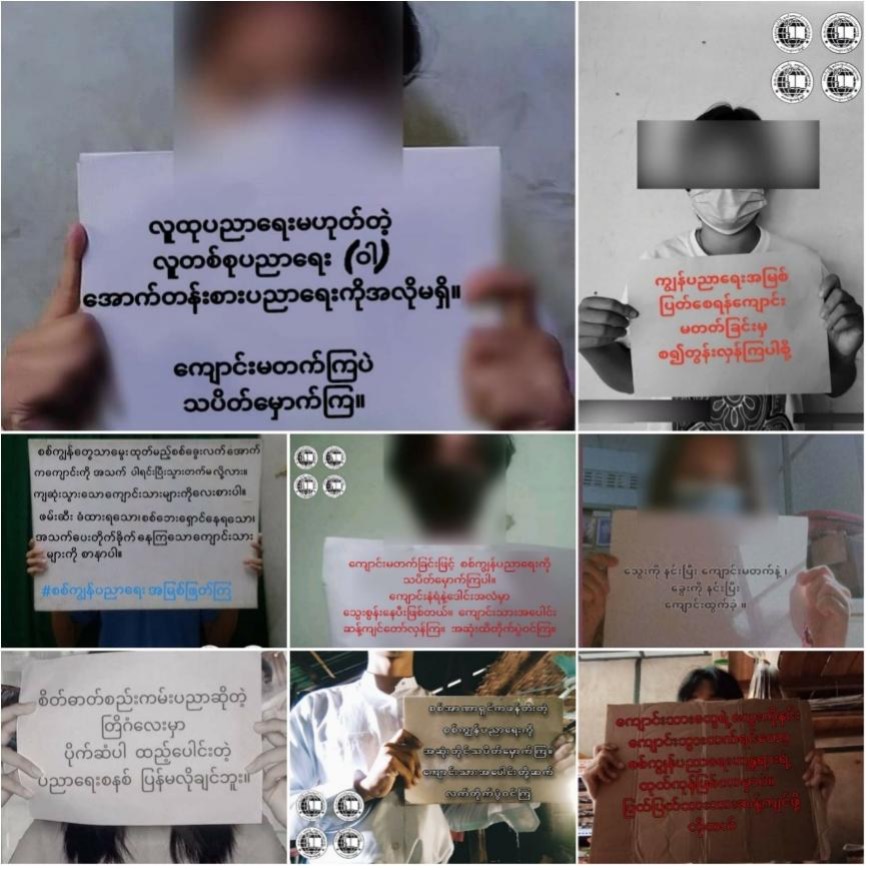

Figure 1. Students against “the military education.” Picture shared on social media.

At the same time, however, they are also imagining a new education system. As Rosalie Metro argues, there are several emerging alternatives to “military slave education” (another historically rooted motto), all based on principles of federalism and self-determination (Metro 2021). So, what does an independent and federal university mean to students? What are their demands for the government and politicians? Most importantly, what is their alternative education model? One proposed model is embodied by the Virtual Federal University (VFU), led in part by members of the University of Yangon Student Union. Three principles underpin the VFU: 1) experiment with a learning and teaching model that will facilitate the federal education system, 2) provide free education, and 3) make students’ voices and demands central to the operation of the university. The VFU seems to interpret federalism in terms of everyday civic actions, including students’ interactions with each other, educators’ views of their students, and the role of classes in promoting self-esteem, dignity, and a sense of belonging to a community. Experiments such as the VFU aim to foster federal conversations and practices and to build a federal democratic country from the bottom up. This process would entail bridging the differences among organizations and individuals from different backgrounds[3] and bringing wider political issues that were sidelined by student unions under the NLD government back into the conversation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we are witnessing a fight between students and academics on the one hand and the SAC and the Tatmadaw on the other hand over the future of Myanmar’s universities. The core of this confrontation is represented both by the future of younger generations, who are already facing a two-year hiatus on their educational path, and by the possibility to establish a higher education system that either can have a transformative power (possibly represented by the visions for a federal education) or is destined to reinforce the military state’s authority. In the introduction, our first question was about the new mission of higher education within the SAC state project; the “new” visions are, in fact, the “old” Tatmadaw recipes. The SAC seems determined to being the country back to the days when higher education was spatially and administratively fragmented and cognitively separated from society at large. The SAC is actively working against the recent higher education reform that, among several difficulties and limitations, was seeking to improve the higher education system of the country founding Myanmar’s future on university autonomy, national academia with a place in the global scientific arena, and down the line a more just society. Interestingly, the SAC seems to believe that the old ways would still work, even if students and academics, in particular, are proving that after a decade of transition, they have acquired different visions for transformative higher education and a far better understanding of what a more just Myanmar could look like.

To a certain extent, the SAC’s actions have already (re)created divergences in everyday life in university spaces. For example, a conflict has arisen between CMD staff and those who have decided to maintain their positions. Academics in the two camps are expressing different perceptions of what constitutes the most honorable and suitable thing to do for Myanmar’s future and current students. The bond and relationship of trust between and among students, teachers, and families has once again been broken, like during the previous military period. SAC actions are (re)shaping a climate of political violence, fear, and vulnerability that is causing teaching staff and students in Myanmar universities to perceive themselves as targets of oppression and scrutiny. The light in the darkness is represented by the conversations on federalism and practices in education that students and academics are investigating, aimed at building up a federal democratic country from the bottom. These conversations and experiments can lay the foundations for the restructuring of a new national higher education system if and when a new policy window for change eventually re-opens.

References

- (1989), “Perspectives on Student Political Activism,” in Altbach, P.G. (ed.) Student Political Activism: An International Reference Handbook. New York: Greenwood Press, 1–17.

- (2013), Technical Annex on the Higher Education Subsector, Myanmar Comprehensive Education Sector Review (CESR), Phase 1: Rapid Assessment. Available online at: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-document/79491/46369-001-tacr-04.pdf.

- (2008), “Evolving Education in Myanmar: the Interplay of State, Business and the Community,” in Skidmore, M., and Wilson, T. (eds), Dictatorship, Disorder and Decline in Myanmar, Canberra; ACT: Australian National University Press, 127–150.

- (2016), “Students and Teachers as Agents of Democratization and National Reconciliation in Burma: Realities and Possibilities,” in Egreteau, R., and Robinne, F. (eds), Metamorphosis: Studies in Social and Political Change in Myanmar, Singapore: NUS Press, 209–233.

[1] Our governmental sources stated they have started to hire student as tutors to replace the missing professors.

[2] The Milk Tea Alliance is an online democratic solidarity movement connected to Hong Kong, Thailand, Taiwan, and Myanmar. It pushes back against Chinese domination in the region and aligns itself with other global anti-authoritarian/pro-democracy movements such as various country-based Spring Revolutions. Protesters in Thailand and Myanmar have adopted the three-finger protest salute from the fictional Hunger Games movie series as a sign of resistance by people facing injustice everywhere.

[3] One fact is particularly interesting in relation to this issue: in March 2021, various universities in Mandalay issued statements apologizing to Rohingyas and other minorities for having failed in the past to speak up on their behalf over human rights violations. The Rohingya crisis had not been one of the grievances central to student politics during the transitional period, but it is now part of the debate, and this overall debate is gaining new language linked to human rights and federalism.

“L’amministrazione Biden ha detto di considerare gli atolli e gli isolotti controllati dalle Filippine nel mar Cinese meridionale all’interno del campo di interesse del... Read More

Nell’ambito della visita di Stato del Presidente della Repubblica Sergio Mattarella nella Repubblica Popolare Cinese, conclusasi il 12 novembre scorso, è stato rinnovato il Memorandum of... Read More

“Pur avvenendo in un contesto senz’altro autoritario e repressivo, questo tipo di eventi non vanno letti per forza come atti di sfida nei confronti... Read More

“The Chinese leadership has likely assessed that the Americans will keep up the pressure, so holding back is pointless. China is therefore likely prepared... Read More

“For the Trump administration, China’s being defined not as a rival, but as an enemy. It would be interesting to understand the effect of... Read More

Copyright © 2024. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved