In October 2020, Japanese prime minister Suga Yoshihide chose Vietnam and Indonesia as the destinations of his first official visit abroad.

From a security standpoint, there is little doubt that the two countries play a crucial role in the Japanese–American grand strategy, launched by Suga’s predecessor, Abe Shinzō, of building a Free and Open Indo-Pacific to counter China’s assertiveness. Security, however, is just one element of a more intricate puzzle of competition and cooperation between Tokyo and Beijing in this region of Asia.

Suga’s trip to Southeast Asia (SEA, hereafter) was also chosen as the occasion to unveil his government plans to make Japan carbon neutral (i.e., to slash the country’s emissions to a level that can be absorbed by nature) by 2050. During a press conference in Jakarta, Suga announced that his cabinet would work to enhance the country’s industrial and administrative systems, promoting the use of digital technologies while cutting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Tokyo’s vow to curb emissions parallels those of the European Union, the UK and China, which, according to the statements of its president, Xi Jinping, will become carbon neutral by 2060.

Apart from its obvious – though yet to be seen – domestic consequences, Suga’s pledge will likely have an impact on Japan’s diplomacy with SEA.

Since the mid-2000s, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), covering a region with a total population of 635 million people, nearly half of whom live in urban areas, has launched a series of initiatives in the field of environmental sustainability, identifying cities as key areas of intervention. Coincidentally, Tokyo has been supportive of the region’s efforts to narrow development gaps among member states and to tackle emerging challenges, such as climate change and disaster risk reduction. In 2011, for instance, the government of Japan (through the Japan–ASEAN Integration Fund (JAIF), set up in 2006 by the Koizumi cabinet to strengthen Japan’s economic and cultural ties with SEA) allocated resources in support of a specific ASEAN programme on ‘environmentally sustainable cities’.

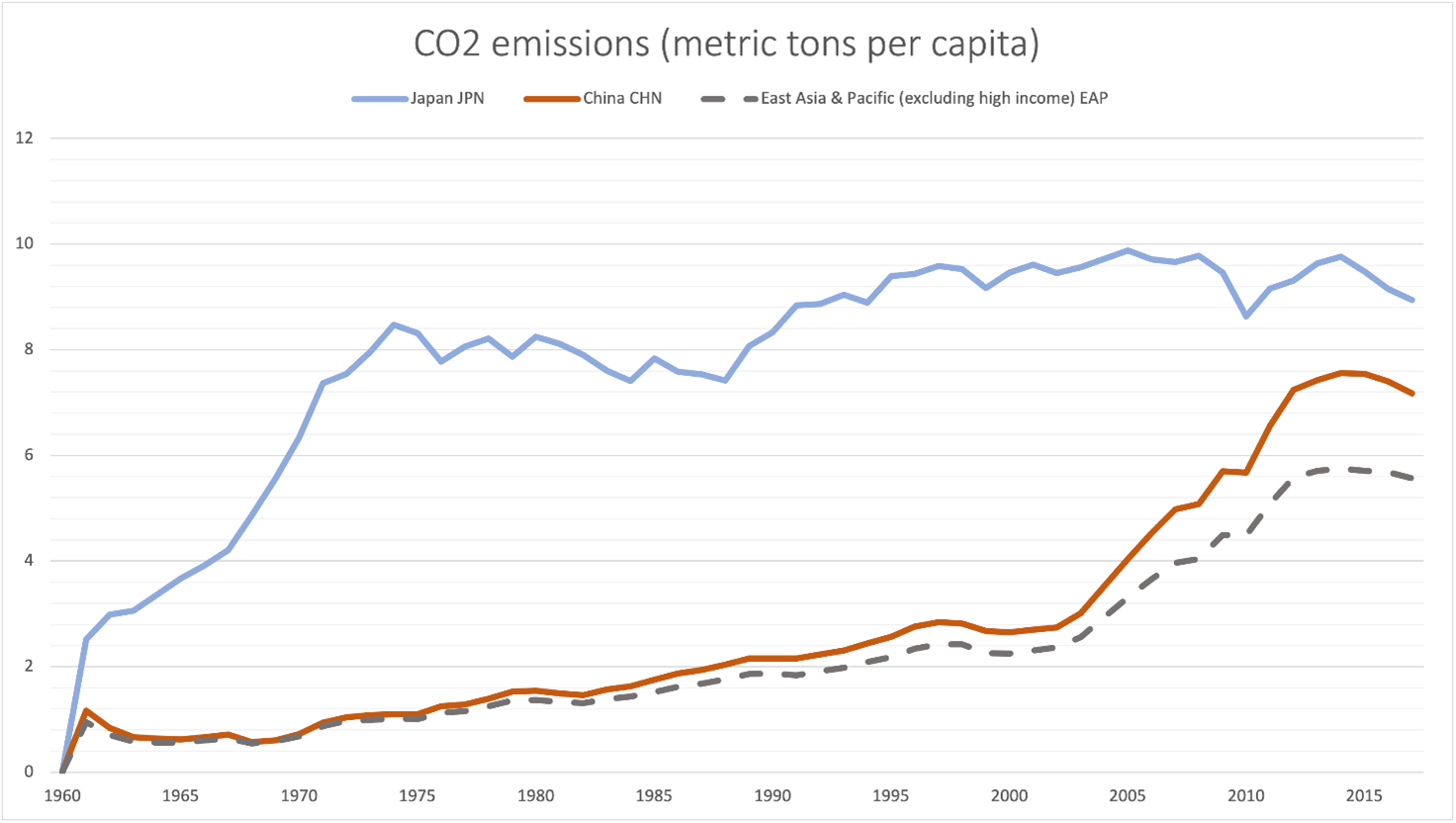

This infographic shows the CO2 emissions in the Asia Pacific region (Source: World Bank)

More recently, just after adopting the Paris Agreement on Climate Change in December 2015, Tokyo also adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and committed to reducing GHG emissions by nearly a third of the 2013 level within the next decade, in order to facilitate regional and global environmental sustainability. Against this backdrop, and following the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, in 2018 Japan became the largest donor to the Green Climate Fund, created within the framework of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to assist developing countries in need of financial means to make the transition to ‘clean’ and more efficient energy sources.

The private sector will likely play a role in this process. In January 2020, Son Masayoshi, founder and president of the Japanese telecom giant SoftBank, met with Indonesian president Joko Widodo to discuss the company’s involvement in a USD 32.7 billion smart city project for the new capital to be built by 2024 in East Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo). With the current capital of Jakarta literally sinking due to rising sea levels and over-extraction of underground water, the Indonesian president is keen to speed up the relocation of the seat of government and welcomes investments from SoftBank, which has pledged both to support renewable energy and electric vehicles, and to expand the Indonesian operations of the popular ride-hailing/food-delivery/digital wallet app Grab.

Such activism is welcome in Nagatachō. Over the past few years, Tokyo has placed particular emphasis on infrastructure system exports as the key to revitalizing the Japanese economy. Laying out the country’s infrastructure strategy in 2016, former prime minister Abe stressed that ‘the promotion of … Japan’s high-quality infrastructure to meet expanding global infrastructure needs is crucial to Japan’s economic growth, and helps construct win–win relationships’. Japan’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) has been instrumental in this strategy. As reported by the latest ODA White Paper, in 2018 Tokyo disbursed USD 11 billion in economic infrastructure and service development (slightly less than 60% of the total allocated budget for international cooperation).

Of these funds, ASEAN has absorbed nearly USD 2.3 billion, which places the region among the largest recipients of Japanese aid.

While this approach may have geopolitical significance in countering China, it also helps to create alternatives for manufacturers faced with the limitations of a shrinking domestic market.

Besides being a key exporter of raw materials, SEA is in fact a major market for Japanese exports, and particularly infrastructures for power generation, including gas- and coal-fired energy systems. In this regard, a number of coal plant projects co-funded by Japanese public and private actors have cast a shadow over Tokyo’s international credibility as an international leader in fighting climate change in recent years.

With the justification of responding to growing demand for electricity, Tokyo has provided, over the course of the last decade, two aid loans of USD 1.8 billion and USD 636 million to the governments of Indonesia and Vietnam, respectively, to build two coal-fired power plants in Indramayu, West Java, and Vũng Áng, in Hà Tĩnh province, Central Vietnam. These two projects have caused local resistance and attracted international criticism on account of a number of issues, including the non-implementation of the best available technologies to reduce pollutant emissions.

Another 1,320 MW coal-fired power plant, Vân Phong 1, in South Vietnam, whose construction is supported by Japanese international cooperation, is nonetheless scheduled to be completed in 2023.

Coal burning is a notorious cause of global warming and air and water pollution, with direct impacts on human health. In spite of this, SEA’s coal demand is predicted to grow over the next few years.

Here lies a fundamental aporia in Japan’s infrastructure diplomacy that Suga and his successors will have to overcome if Japan is to honour its climate change commitments. International pressure in July 2020 led to a pledge by Environment Minister Koizumi Shinjirō (poised to be Japan’s future PM) to reduce aid quotas for polluting coal plants in favour of more efficient state-of-the-art power generation technologies.

ASEAN’s growing demand for knowledge and technologies that might help to strengthen the region’s capacity to adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change, as indicated in the organization’s long-term strategy for the development of an ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC), is putting pressure on Japanese manufacturers and tech companies to reorient their strategies. In February of this year, Mitsubishi Corporation, one of Japan’s major general trading companies, withdrew from a third USD 2 billion coal plant project in Vietnam – Vĩnh Tân 3 – after other financiers, including the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, pulled out, signalling a shift toward financing ‘less environmentally harmful’ power projects.

Tokyo needs to be ready to support this shift with a consistent and lasting set of policies. What is at stake is not losing to China, but rather the survival of Japanese companies in an increasingly competitive landscape.

Author

Marco Zappa is Assistant Professor at Ca’ Foscari University Venice and Adjunct Professor at the University of Torino.

Download

Copyright © 2024. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved