After years, sometimes decades, of civil war, the temptation to treat the formal signing of peace agreements as the culminating endpoint in the struggle for ‘just and lasting’ peace has often, and for good reason, proved strong. The tendency to view the handshake moment also as a watershed moment has only been reinforced by the high-flown language and grand promises contained in the agreements themselves. When it comes to the actual afterlife of peace agreements, however, the contrast between promise and reality has often been stark. The truth is that peace agreements reached following civil wars over the past thirty years have rarely lived up to the promises enshrined in the agreements, let alone the hopes for societal transformation and ‘positive peace’ adumbrated at the time of their signature.

At first sight, this divergence between promise and delivery is liable to induce cynicism and despair in equal measure. And yet, evaluating the afterlife of peace agreements cannot be reduced to a crude ticking-off exercise in which peace implementation is measured in some mechanical fashion against a long list of formally agreed objectives. To do so would be to misunderstand the functions and purposes of peace agreements as well as the manner in which they are arrived at. Nor would such an approach help much when it comes to unpacking the relationship, direct and indirect, between the contents of peace agreements and the trajectory of political, military and socio-economic developments following their signature. To disentangle that relationship, it is necessary to consider, in each individual case, the interplay of three elements: (1) the contextual factors and political realities that help shape the agreement in the first place and which continue, in mutated form, to influence its implementation; (2) the details and provisions of the peace agreement itself; and (3) the choices made by parties, external actors and guarantors while implementing the agreement. The record and long-term viability of any given peace agreement is a function of all three elements.

Thus viewed, it is clear that peace agreements cannot by themselves deliver just and lasting peace. Even so, peace agreements clearly do matter. Poorly designed and inadequately supported, they can deepen and entrench pre-war patterns of conflict, exacerbate intra-elite competition, accentuate both socio-economic and political grievances, and, ultimately, open new fissures within societies. By contrast, an agreement that is properly designed, adequately resourced, and underpinned by consistent and constructive political support from interested parties, regional players and international sponsors, can serve to strengthen the political forces and dynamics that favour long-term stability and encourage societal transformation towards a deeper, more truly self-sustaining, peace.

What, then, are the functions and purposes of peace agreements? Against what kind of qualitative criteria should their contribution to building peace be evaluated? The post-Cold War history points to three broad contributions for peace agreements in the process.

First, peace agreements can help control and reduce levels of violence and insecurity by weakening structural incentives for resorting to violence as a means of resolving political differences and/or advancing criminal and economic agendas. In part, this can be encouraged through concrete steps: disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration; security sector reform; the creation of monitoring mechanisms, and the rebuilding of law and order institutions. Actions in any of these areas represent deeply political interventions whose design must take account of the underlying political economy of conflict lest they produce perverse and unintended consequences. Equally if not more important, however, are the steps taken to ensure that the new political space and ‘rules of the game’ created by a peace agreement encourage rather than undermine the growth of moderate and progressive political forces and dynamics in favour of long-term stability.

Second, peace agreements can provide mechanisms for conflict resolution, including fixes and face-saving formulas for overcoming seemingly intractable obstacles to progress. An instructive example is provided by the creation of the Supreme National Council (SNC) in the Paris Agreements for Cambodia. Composed of all four factions to the conflict, including the Khmer Rouge, the SNC was presented as the embodiment of national sovereignty when, in truth, it was a largely symbolic devise designed to make an agreement possible.

Third, peace agreements can help build confidence in the future and provide the beginnings of transformative societal change. The function of an agreement in this sense is less about resolving outstanding issues than identifying common interests and exploring the possibilities for coexistence.

It follows from the above that there is no simple or easy way of benchmarking success when it comes to peace agreements and their afterlife. Indeed, discussing, let alone defining, ‘success’ in any meaningful sense is impossible without an appreciation of the wider context – historical, political, cultural and normative – within which a given agreement was negotiated, concluded and implemented. Ascribing post-signature developments to flaws inherent in the text of peace agreement may be unfair where implementation is undermined by an unfavourable regional setting from the outset; where it is crippled by limited resources; and, most important of all, where it is up against a fundamental lack of commitment on the part of key stakeholders. Nor are there any fixed or ready answers to questions about the appropriate length, level of detail, and degree of inclusivity of an agreement. Again, meaningful answers to such questions depend critically on context.

In the end, authoritative and less provisional judgements about the contribution of peace agreements to building peace after civil wars require a longer-term historical perspective, formed in response to a broader set of questions:

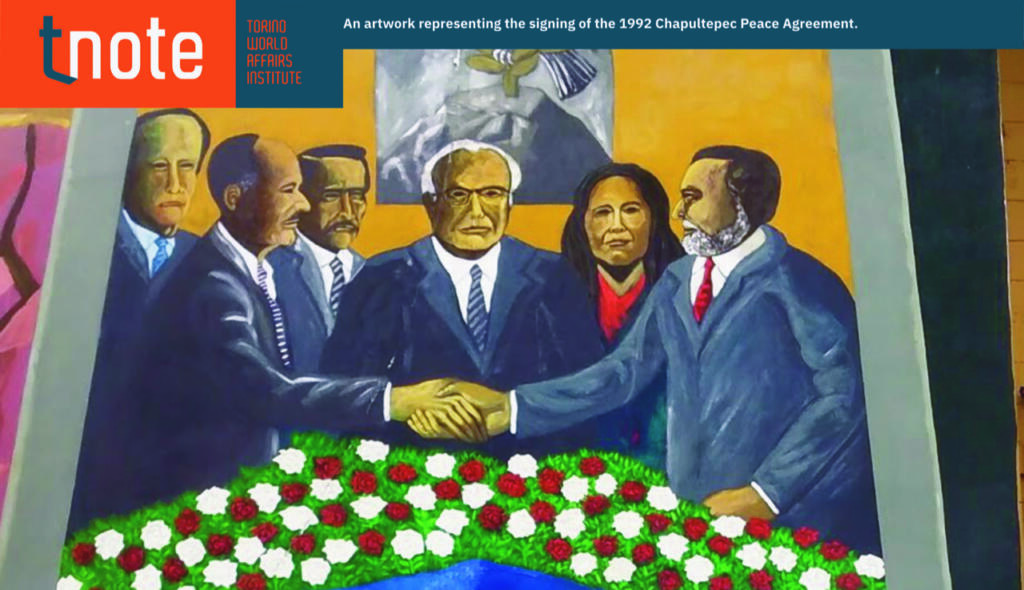

Even these questions leave room for differing, though not necessarily incompatible, conclusions and perspectives. In Mozambique, the UN, anxious to avoid a repeat of the catastrophic collapse of the 1991 Bicesse Peace Accord in Angola, successfully monitored and verified the implementation of the 1992 Rome Agreement, including the demobilisation of some 80,000 soldiers, the creation of new joint army and the organisation of free and fair elections. Since then, four more presidential and parliamentary elections have been held. Over the same period, however, economic growth has utterly failed to generate wider, more inclusive, socio-economic benefits. The case of El Salvador is widely treated as a success story in the peacebuilding literature, and there is no denying the gains made as a result of the 1992 Chapultepec Peace Agreement. Chief among these has been the high degree of political stability brought to the centre of national politics with former arch-enemies contesting elections at regular intervals and, crucially, abiding by their outcome and legitimacy. For all this, profound structural inequalities and entrenched power structures persist. Not only do peace agreements signal the start as much as the end of peace processes, but peace itself, in Oscar Arias Sánchez’ perceptive formulation, “has no finishing line, no final deadline, no fixed definition of achievement”.

*This T.note draws on a more extensive analysis provided in Berdal, M. (2021) “The After Life of Peace Agreements” in: Weller, M. et al. (eds.) International Law and Peace Settlements.

Author

Mats Berdal is Professor of Security and Development in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, where he is also the Director of the Conflict, Security and Development Research Group (CSDRG).

Download

Copyright © 2024. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved