In February 2021, Myanmar’s generals ended their own experiment with electoral democracy and staged a coup against the re-elected civilian government. Since then, violence has engulfed a country that is already home to the world’s longest ongoing civil war between ethnonational rebel movements – known as Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) – and the military of an ethnocratic state – the Tatmadaw. As the conflict is largely confined to the country’s far-flung peripheries, observers and policymakers alike have often relegated it to a second order priority. In the wake of the coup, however, EAOs have come into the spotlight in Myanmar politics.

Some observers have even declared EAOs to be the ‘real kingmakers’ of this crisis as both the military and the civilian resistance movement – as represented by the National Unity Government (NUG) – are vying for EAO support. The positioning of EAOs themselves, however, is far from clear. Some are supporting popular resistance to military rule and allied themselves with the NUG. Most importantly, the Karen National Union (KNU) and the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) have both stepped up their military engagement with the Tatmadaw, and both shelter revolutionaries from central Myanmar, and provide guerrilla training for young activists fleeing from the cities. Other EAOs, such as the Arakan Army (AA), seem to be hedging their bets and retaining strategic ambiguity towards recent developments. Still others, such as the United Wa State Army (UWSA), have affirmed their pragmatic ceasefire relations with the Tatmadaw.

To explain all variation in EAO positioning towards the new realities in Myanmar is beyond the scope of this T.note. A commonly heard and important point in explaining the general wariness of EAOs in their engagement with the NUG, is that EAOs view the current crisis in Myanmar as essentially a conflict between the forces of the country’s ethnic Bamar majority. While the NUG’s backbone – the National League for Democracy (NLD) – is fighting for democracy, EAOs and many of their ethnic nationality constituents had a rather dire experience of the past ten years of democratization. Throughout this time, ethnic conflict and civil war escalated but no progress was made on EAOs’ political demands surrounding federalism, power sharing and ethnic minority rights.

In line with this, there is also a profound sense that history is currently repeating itself, and history has hitherto not been on the side of EAOs. The Karen National Union (KNU) for instance was a crucial ally of the NLD-led pro-democracy movement in the 1990s and 2000s. Much like today, the KNU sheltered activists from central Myanmar, trained Bamar youth in armed resistance, and vowed support for the NLD-led exile government of the time. Much like today, the KNU paid dearly for its support as it came under heavy attack by the military, whose ruthless counterinsurgency campaigns resulted in a humanitarian catastrophe for the Karen people and the loss of crucial territory for the KNU. After the NLD made its way to power, however, many in the KNU felt as if their erstwhile allies threw them under the bus.

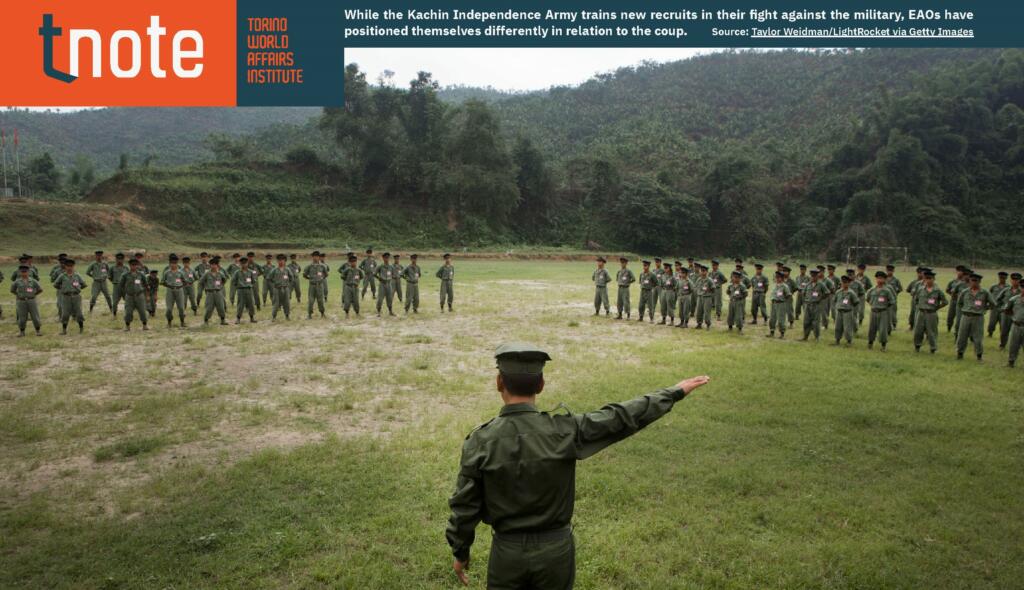

While the Kachin Independence Army trains new recruits in their fight against the military, EAOs have positioned themselves differently in relation to the coup. Source: Taylor Weidman/LightRocket via Getty Images

Why then would the KNU support the NUG today? From a purely strategic perspective, the KNU might better be advised to hedge its bets, as does the AA. It appears that some of the movement’s leaders, including the KNU Chairman Gen. Mutu Say Poe and the KNLA’s Chief of Staff Saw Johnny, were indeed inclined to do so. But the strategic outlooks, decisions and overall trajectories of EAOs cannot simply be reduced to decision-making on a leadership level. As I argue in my book Rebel Politics, EAO strategies are instead best understood as the result of multifarious and often contentious relations between differently placed actors of heterogeneous movements that reach deep into wider society. This perspective suggests that one particularly important axis of analysis for understanding EAO politics is that of the vertical relations between EAO leaders and their grassroots, including rank-and-file members as well as wider activist networks and ethnic nationality constituents. In other words, upward pressures matter for the strategies of EAOs.

Arguably, the positioning of the KIO and the KNU in support of the NUG was shaped by those grassroots pressures. After the coup, Kachin and Karen communities joined the nationwide resistance against military rule. Like other protesters from Myanmar’s diverse ethnic nationality communities, they did not seek the reinstitution of the same democratic system that led them down before. Instead, ethnic nationalities took to the streets to call for a complete overhaul of Myanmar’s ethnocratic state and society, demanding for federalism and ethnic minority rights. They demanded for the political aims that EAOs, including the KIO and the KNU, have long been fighting for. The KIO and the KNU consequently made their first move towards supporting the wider revolution in Myanmar by vowing to defend protesting civilians in Kachin and Karen States from security forces.

This is not to say that Rakhine, Shan, or Wa or others have not been participating in resistance against the military. Of course, they have. In fact, ethnic nationalities up and down the country have been a central pillar of Myanmar’s diverse revolution from the outset. Here, however, my argument that EAO strategies are shaped by grassroots demands needs an important caveat: the degree to which upward pressures matter for EAO strategies, depends on the nature of vertical relations between EAO leaders and their grassroots. The Karen and Kachin rebellions, for instance, have a long tradition of civic engagement, including regular public consultations with community representatives. The KNU and the KIO can thus be understood as parts of wider revolutionary Karen and Kachin movements. These movements are inhabited by community-based organizations, activists and other authorities, such as local churches or diaspora networks. The debates that unfold within their revolutionary public spheres involve critical engagement with EAOs, their leaders and their decisions.

In both the Karen and Kachin rebellions, grassroots demands have indeed often been more resolute than those from parts of their EAO leaderships. Most recently, we have seen this play out in the case of the Karen rebellion. When KNU Chairman Gen. Mutu Say Poe and individual leaders close to him repeatedly suggested a return to the widely criticised Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), the pushback they encountered did not come only from other parts of the KNU. Importantly, they also met an outcry from Karen civil society organizations, as was also the case when Gen. Mutu signed the NCA in the first place. This contrasts with EAOs who have been less supportive of the present revolution in Myanmar. Again, there are multiple factors at play, and we should not oversimplify things. For instance, the UWSA has unchallenged control over its territory in which it can effectively provide protection for local communities. This is not the case for the KNU or the KIO. At the same time, however, it is not far-fetched to argue that EAOs such as the UWSA or the Shan State Progress Party (SSPP) have less developed public spheres. Grassroots pressures thus shape their strategic manoeuvring to a lesser degree than is the case in the KNU and KIO. That said, social foundations matter in all of Myanmar’s ethnonational movements, including the officially recognized EAOs and beyond. This was most pressingly demonstrated by heavy fighting that has erupted in Chin and Kayah States in the wake of the coup. While both regions are home to small EAOs, the Tatmadaw has been challenged by grassroots-organized rebellions in communities that have suffered continued marginalization and militarization throughout the past decade of democratization. Their bravery and sacrifices should urge us to pay more attention to the social foundations of armed struggle more generally.

Author

David Brenner is Lecturer in Global Insecurities at the University of Sussex. He is author of Rebel Politics: A Political Sociology of Armed Struggle in Myanmar’s Borderlands (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2019).

Download

Corso Valdocco 2, 10122 Torino, Italy

Sede legale: Galleria S. Federico 16, 10121 Torino

Copyright © 2025. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved