The overabundance of works seeking to explain “the rise of China” to the general public has increased the chances of stumbling on publications that rest on shaky academic foundations. With most popular books offering limited analyses on selected aspects of China’s rise, it is increasingly difficult to find works that provide insightful views on China’s domestic and international growth. One exception to this general trend is Everything Under the Heavens: How the Past Helps Shape China’s Push for Global Power by Howard French.

The idea behind French’s work is as simple as it is effective. It consists of going through the history of China’s imperial and contemporary foreign policy with the goal of detecting its ideological underpinnings and identifying the fil rouge that links China’s glorious past with its present and near future.

While the book is full of little-known facts and original thoughts, three points in particular make Everything Under the Heavens a must-read. First is French’s analysis of the concept of Pax Sinica. According to French, China reappeared on the global economic stage in the 1980s, at a time when the US-led international order had reached its pinnacle in terms of development and global influence. China has been socialised into this order ever since. Yet, a series of signs indicate that this may no longer be the case. One way to make sense of this tendency is by bearing in mind that, prior to descending into what the author calls its “historical nadir” in the 19th century, China was the hegemon and patron of its very own world order. China would recognise the political legitimacy of other countries and establish trade relations with them, in exchange for these countries’ acceptance of its superiority. In this regard, the author provides an insightful reinterpretation of the voyages of Admiral Zheng He. While Chinese authorities, all the way from Sun Yat-Sen to the current leadership, used the story of Admiral Zheng as evidence of China’s peacefulness and moral superiority vis-à-vis Western colonial powers, a closer look at the historical records shows that China’s relations with its neighbours were far from being friendly and non-aggressive. Given that Chinese rulers sent Zheng around the world to tell local kings, sultans and rulers that engaging with China and trading with it were “offers they could not refuse”, it becomes clear that “Zheng’s legend as an ambassador of goodwill and friendship simply doesn’t hold up. It is Chinese idealization, not history” (p. 101).

The second aspect of China’s historical path analysed in the book is the series of foreign policy narratives (supposedly built on historical precedents) employed to frame China’s current re-emergence. These include the idea that China’s rise will be inherently peaceful, given that China has never established colonies abroad in the past and that, at present, it is merely interested in entertaining trade relations with its partners, without seeking to transform its economic influence into political leverage. The author dismisses all such myths by quoting several examples (some of which are little known) that reveal a series of opportunistic, intimidatory and underhand behaviours adopted by Chinese authorities and representatives throughout history: the Song betrayal of the Indonesian city-State of Srivijaya in the 11th century, the invasion of Sri Lanka by Admiral Zheng in 1411, and the recent cover-up of the military construction activities in the South China Sea. Howard French thus portrays China as an ultra-Machiavellian power seeking to regain its rightful place in the current world order, far from being a peaceful and harmless defender of underdeveloped and developing countries alike.

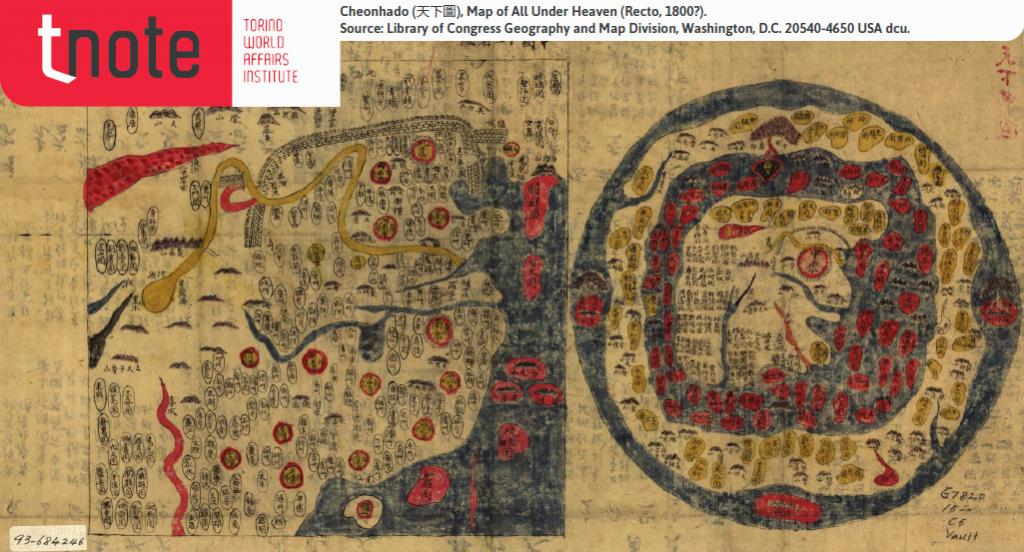

The third key point French raises is a direct consequence of the first two and it can be expressed in the form of a question: are China’s contemporary foreign policy efforts aimed at re-establishing a new form of tianxia? While the term has never been used by Chinese diplomats in modern times, there is no doubt that China has grown more proactive and vocal in the pursuit of its interests across Eurasia and beyond. As the author says, “the problem for us is that China believes in a tributary system; that is the normal order of things” (p. 30). In its original version, the new tianxia would be composed of concentric areas of influence: a near periphery assimilated into China, an intermediate periphery to be substantially assimilated into China’s economic and political influence over time, and further parts of Asia, which, while impossible to assimilate, are not immune to China’s economic and political influence.

While French contributes to a decade-long debate on whether China’s re-emergence on the global stage comes with a normative agenda, the novelty of his book lies in the use of an eclectic and multifaceted approach to the study of how China is already working towards shaping the international order in ways that could suit its most pressing interests. In light of this, the concepts of the China Dream and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) could be seen as attempts to craft propaganda that paints a new world order that recognizes China as its core.

The effects of this paradigmatic shift, I would argue, are visible not only across the realm of politics and international relations, but also across those of business, law and finance – sectors that lie at the heart of the T.notes’ CMBP Series. As an example of this, one could think of the series of state-orchestrated mergers set up to create global leaders in key industries, or Anbang’s de facto nationalisation, suggesting a return to statism despite repeated promises by Chinese leaders to leave room for market liberalization. One could also think of the recent changes to the Constitution, or the establishment of special litigation courts along the BRI. Last but not least, examples from the financial sector include the consolidation of financial regulatory powers, or the return of a negative trend of additional capital controls.

While these examples may appear to be scattered, the upcoming CMBP T.notes will analyse them in light of the theoretical framework employed in Everything Under the Heavens. The question to be answered is not really whether China is developing a new world order, but what the future world order will look like in light of China’s skilful use of its tools of economic statecraft.

Download

Copyright © 2025. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved