Less than thirteen years after the onset of the ‘Great Recession’ in 2007–2008, the world has been newly overwhelmed by an economic crisis, although this time it is a crisis triggered by an exogenous agent and not the result of financial imbalances. As a significant worldwide shock, the COVID-19 crisis reshapes developing trajectories and geo-economic priorities, strengthening some trends and undermining others.

In this altered scenario, it is stimulating to provide insights and hypotheses on the future development of a significant and much-discussed financial institution that was born in the last decade: the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB).

The AIIB is a China-initiated medium-sized multilateral development bank (MDB), founded in 2014 by seventy countries with initial capital of USD 100 billion, in which China holds right of veto because it has 26.52% of total votes.

At the beginning, the credit facilities provided by the AIIB were supposed to finance mainly the infrastructural projects involved in the six Eurasian corridors of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), but since 2016 several Chinese officials have started to distance the Bank from the BRI development.

Four years after the first loans were granted, the questioning of the form of globalization espoused by the Trump administration, embodied by the ‘trade war’, combined with the current COVID-19 crisis, provides an opportunity to briefly assess AIIB activities so far. In particular, we should focus on how sectors and countries are being financed in order to formulate some hypotheses on the Bank’s future capability to promote its aims in a fast-changing scenario.

AIIB’s recent developments and the loans issued reveal both its autonomy from the BRI and its commitment to performing two main functions: securing China’s energy supplies, and improving relations between countries through win-win opportunities in closing the Asian infrastructure funding gap.

Moreover, the Bank is proving to be responsive to unforeseen shocks, as evidenced by the establishment of the ‘AIIB COVID-19 Crisis Recovery Facility’, a credit line for health investments aimed at addressing members’ needs during the pandemic.

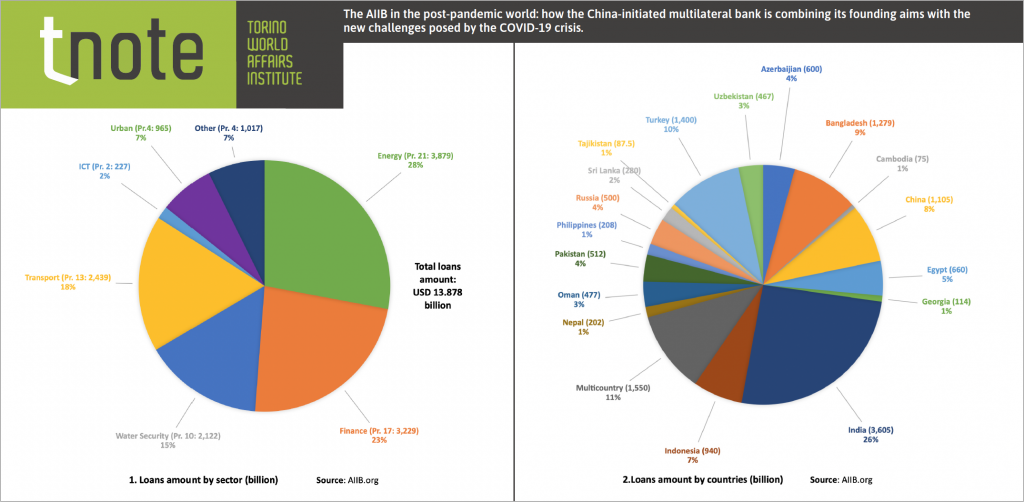

From 2016 to May 2020, the Bank issued seventy-one loans, of which thirty-two were co-financed by other international financial institutions, totalling USD 13.878 billion (see Chart 1).

Energy accounts for 28% of the loans; it has the highest share in terms of both projects and funds, but this percentage nonetheless belies the importance of this sector in AIIB priorities. Three loans recorded as being in the finance sector and others listed as ‘transport’ are in fact linked to energy provision: the Bank is aiming to be a reliable partner to channel investment into the development of renewable energies across Asia, while several ‘transport loans’ concern infrastructure for the transport of energy.

This emphasis on energy is not surprising and can be analysed by combining economic and geopolitical arguments. Energy provision at the lowest possible cost has been a key gear of China’s spectacular growth, making it the largest importer of energy and a significant polluter worldwide. The Bank combines its aim of securing China’s energy supplies with its desire, mainly rhetorical, to be seen as a champion in the shift away from the fossil fuel paradigm towards renewable energy (the motto of the Bank being ‘Lean, Clean and Green’). The attention to climate change and environmental issues is assuming growing relevance within Communist Party policies and becoming an important pillar of China’s global vision, especially in the wake of the withdrawal of the Trump administration from the Paris climate change agreement (COP 21, 2015).

At the geopolitical level, the growing pressure exerted by the Trump administration on China (and Iran) has caused China to clearly redefine its national security strategy and strengthen its emphasis on energy safety. Surging investment in the creation of reliable ‘energy corridors’ through mainland routes seems to be intended to increase energy security, making China less dependent on maritime routes, where the US still has a powerful military edge. If, as argued by Shi Yinhong, the COVID-19 crisis is pushing US–China relations to ‘the lowest point since 1972’, it is reasonable to suggest that the AIIB will continue with its practice of diversifying energy supply lines.

As mentioned above, a second relevant role performed by AIIB is that of deepening Asian economic relationships and improving external perceptions of China’s foreign policy. The Bank has now grown to fifty regional members and 102 worldwide, and thirty-eight of the seventy-one approved projects (54%) involve twenty-two Asian countries, among which India, Indonesia, Turkey, Bangladesh and Pakistan stand out. This renewed relationship with densely populated countries – the above-mentioned five states have 2.075 billion inhabitants (World Bank Data, 2018) – is consistent with China’s goal of deepening inter-Asian ties in order to create new trade opportunities and reduce its chronic export dependency on Western countries.

In this regard, the case of India may prove particularly explanatory of how the win-win opportunities provided by the Bank can positively affect external perceptions of China’s foreign policy. Although India has historically had conflicting interests with China and also shows a certain scepticism about the BRI, in January 2016 it joined the AIIB, underwriting USD 8.3 billion (8.6% of the total fund), and so far it has confirmed 16 projects and obtained 26% of the total loans (USD 3.065 billion; see Chart 2). The transnational infrastructure projects offered by the AIIB are proving to be an effective tool in enabling the interests of rival regional players to converge, giving concrete reality to the win-win opportunities of Chinese rhetoric. If, as many pundits have observed, the COVID-19 crisis may result in a decisive step in the ‘decoupling process’ between the US and China, we can expect that the upgrading of infrastructure in the Asian economic region will continue to represent a task worth pursuing for Beijing.

Finally, the current COVID-19 crisis allows us to observe how the Bank has addressed an unforeseen shock by trying to gain further credibility among its members. On April 16th the Bank announced the establishment of a ‘COVID-19 Crisis Recovery Facility’ to ‘support AIIB’s members and clients in alleviating and mitigating economic and public health pressures arising from COVID-19’. Within this recovery mechanism, India and China have obtained the first two approved loans, USD 500 million and USD 355 million respectively, while another six members have requested nine loans USD 3.270 billion (Bangladesh, Georgia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Serbia, Turkey). The AIIB COVID-19 Crisis Recovery Facility sets out an overall credit line of USD 5–10 billion to finance both public and private sectors.

In conclusion, the two main functions carried out by the AIIB so far – securing China’s energy supplies and improving ties between Asian economies through infrastructural projects – apparently remain priorities of the Chinese government even in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. Even though the AIIB has demonstrated its responsiveness to the COVID-19 pandemic by increasing its support for its members, it is still too early to evaluate what the overall impact of the current crisis will be on the AIIB’s future developments. In the current gloomy scenario, characterized by the worst reduction in GDP growth for decades, the Chinese Communist Party may be forced to downsize the level of resources allocated to improving Asian infrastructures and economic regional relationships in order to foster efforts to guarantee economic growth in the domestic sphere, an issue that ultimately remains the highest priority of the Party.

—

Author

Dario Di Conzo is a PhD candidate in Political and Social Sciences at Scuola Normale Superiore.

—

Download

Copyright © 2024. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved