More than 190 people died and almost 7,000 were injured in the explosion that occurred on 4 August 2020 in Beirut, Lebanon. The blast was allegedly caused by the accidental detonation of approximately 2,700 tonnes of ammonium nitrate, which had been stored unsafely in a warehouse at the port since 2013, and it caused catastrophic damage to the city, destroying buildings and infrastructure and depriving almost 300,000 people of their homes. Together with hospitals and houses, any sign of normal living conditions has been temporarily erased, in contexts from education to bureaucracy.

The blast – equivalent to an earthquake of 3.5 magnitude – has been included among the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions, alongside other accidents resulting from the detonation of ammonium nitrate, such as the 2015 explosion in Tianjin, China. More than half of the approximately 200,000 damaged buildings in Beirut had their windows destroyed, injuring people in the streets and increasing the risk of burglary and looting, as assessed by the Lebanese Red Cross.

The main priorities outlined by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) comprised access to healthcare and medication, food security, shelter and reconstruction, cash assistance and psychological support. In forty-eight hours, Russia and Iran responded by building field hospitals to ease the pressure on the Lebanese facilities, heavily damaged by the blast. Likewise, other regional actors with ties and interests in Lebanon, such as Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Morocco, Qatar and Turkey, contributed with similar operations.

The United States contributed as well through their agency USAID, pledging USD 17 million in disaster response. Among European countries, France and Italy – the two with the greater interests in Lebanon – consistently contributed funds and medical and food supplies. However, instead of being directed to the government, aid was mostly delivered to hospitals, UN agencies, NGOs and associations active on the ground.

The reasons for this behaviour lie within politics. The first and most evident reason is the inability of the Lebanese government to transparently deal with funds: it ranks 137th out of 198 countries in Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index. The second, more subtle reason is the intention of regional and international stakeholders to increase their presence within the already complex political games in Lebanon.

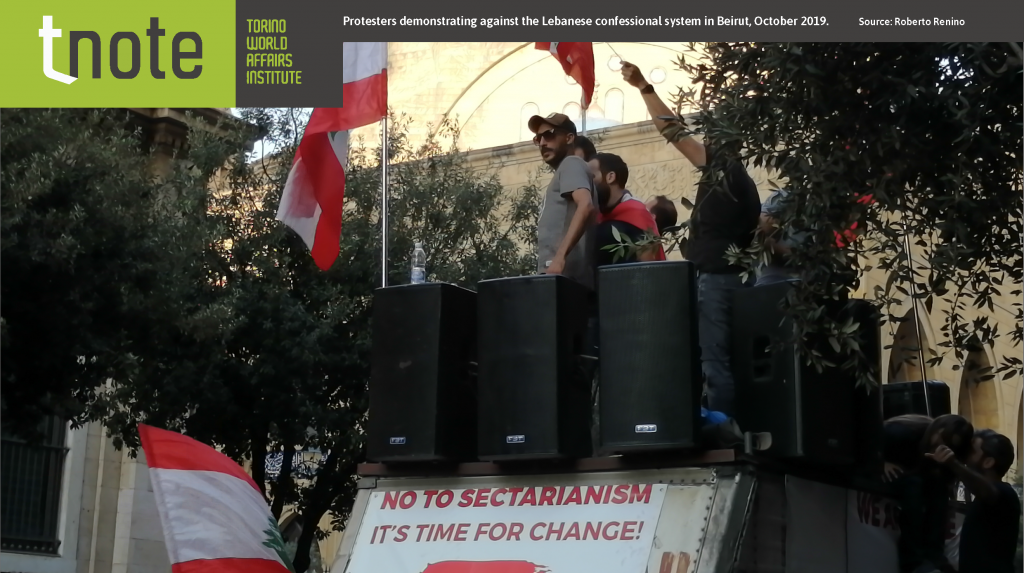

The confessional system on which Lebanon is built offers representation of the eighteen recognized religious sects but paves the way for a regime based on family and clientelist networks, sponsored by foreign actors with interests in Lebanon. The existing status quo, challenged by the protests that started on 17 October 2019, is now also being contested by the foreign actors – especially France and the US – that openly asked the government to apply consistent reforms in order to be held accountable again and therefore restore international trust – and receive international money. Through this mechanism, foreign stakeholders aim to gain a role in the reconstruction: in infrastructure matters, but also, especially, in the restructuring of the political and economic system, which had already begun to default in the previous months.

Protesters demonstrating against the Lebanese confessional system in Beirut, October 2019.

The UN is already present in Lebanon and active on several fronts, most notably through the peacekeeping mission the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) at the southern border and with the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan (LCRP), where several agencies work with the government and NGOs addressing the Syrian refugee crisis caused by the conflict that has raged in Syria since 2011. Through the inter-agency coordination unit created within the LCRP framework, communication and organization for the disaster response have been easier, as a cadre for action already existed. Concentrating partners’ efforts in the city of Beirut, the whole area was divided into operational sectors and entrusted to different actors, according to specific needs and available means. Operations included the restoration of damaged facilities, distribution of food parcels, provision of inclusive health and mental health care for the affected population, and safe shelters for the displaced.

Assessments of need and subsequent distribution of medical and food supplies have taken place among the different districts, prioritizing the most damaged neighbourhoods, where search and rescue missions continued for almost a month. The Lebanese Red Cross (LRC), together with the wider network of the International Red Cross and Crescent (IRCC), has been among the first organizations to be deployed and respond to the emergency. However, a second fire that erupted on 9 September at the port hindered LRC operations: the flames destroyed thousands of food parcels stored in a warehouse, as announced by Fabrizio Carboni, IRCC Regional Director. The fire worsened the general conditions and delayed the rescue operation, as a thick and potentially toxic black cloud covered the city, forcing many to stay indoors.

In parallel with the official operations, thousands of citizens engaged in the search and rescue operations, removing glass and debris from streets and houses, proceeding with assessments and gathering in operational groups around the city. A strong sense of solidarity – already shown during the so-called thawra, the revolution still raging across the streets of Lebanon – made possible the creation of initiatives contributing to the response, such as networks finding shelter for the homeless, and coordinated support for the activities of agencies and NGOs.

In such an environment, response operations should proceed with caution and sensitivity to the issues already affecting a country. Within the current situation, an immediate risk to health is represented by the Covid-19 pandemic, and Lebanon registered a dramatic increase in new cases after the blast, according to the World Health Organization’s official bulletin.

Most importantly, long-term effects are alarming, considering the approach of winter and Lebanon’s total dependence on foreign aid to survive the destruction of the grain reserves stored at the port that vanished in the blast. Moreover, one of the main issues remains the difficulty in assessing and addressing the vulnerable conditions of many, due to the scale of the area concerned and the numbers of displaced people seeking shelter outside Beirut. The blast will have repercussions for the rest of the country as well: rural areas risk falling into deeper marginalization, and millions – including refugees and indigent Lebanese – might see their living conditions worsen.

Despite rapid intervention and a high level of community engagement, the scale of the damage suffered by the city goes beyond the scope of the humanitarian response. First, the tangible damage will take years to be fully repaired and, considering Lebanon’s deep economic crisis, foreign aid is going to be essential. On the other hand, the intangible damage, such as the widening of the regime–people divide, increased polarization within society and the collective and personal psychological trauma, will require a long and complex national path of political restructuring and social reconciliation. However, despite the grassroots mobilization, Lebanon is entangled in a web of interests of several local, regional and international stakeholders, which have often marred the Lebanese status quo, hindering any process of reform and change.

Thus, the management of international aid for the reconstruction of Beirut is problematic: while the government does not seem to represent a trustworthy actor able to manage the funds received, any choice to directly invest in actors in the field might also raise concerns. The absence of common, transparent and accountable monitoring can easily lead to misuse of funds, negatively affecting the reconstruction process.

The fragile government created by Hassan Diab after Hariri’s resignation in 2019 also resigned a few weeks after the blast, and another coalition playing by the same rules will not be able to solve the problem: in Lebanon the whole game must be changed.

Author

Roberto Renino graduated from the University of Torino, Italy, with an MA in International Relations – MENA politics.

Download

Copyright © 2024. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved