In March 2020, as the SARS-CoV-2 virus rapidly spread around the world, UN Secretary-General António Guterres made an impassioned plea for ‘an immediate global ceasefire’. Urgency centred on the uniquely global challenge presented by the pandemic and its potential to compound multiple intersecting forms of insecurity already affecting residents of conflict-zones. The virus would not discriminate between warring sides nor respect territorial boundaries. A global ceasefire, it was hoped, could open-up desperately needed humanitarian corridors and coordinated health interventions. More than this, it might provide an opportunity to reinvigorate peace processes, reducing insecurity well beyond the pandemic.

Within days of the call, armed actors in Cameroon, Central African Republic, Colombia, Libya, Myanmar, the Philippines, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen, made public ceasefire commitments. However, as the Secretary-General warned, ‘there is a huge distance between declarations and deeds’. In practice, that distance has been acutely felt.

Most ceasefires were temporary with the status quo quickly returning when public commitments to peace rang hollow. In Colombia, the National Liberation Army (ELN) rebels declared a unilateral ceasefire starting on 1 April, but later that month announced a resumption of military operations after blaming the government for not restarting peace negotiations. In other cases, armed violence increased. In Libya, violence intensified, with water and electricity services interrupted and key health infrastructure – such as the Al-Khadra General Hospital in Tripoli – damaged. One study tracking these conflict trends noted that although COVID-19 was not directly causing violence, it was ‘playing into existing conflict fault lines and threats to peace processes’.

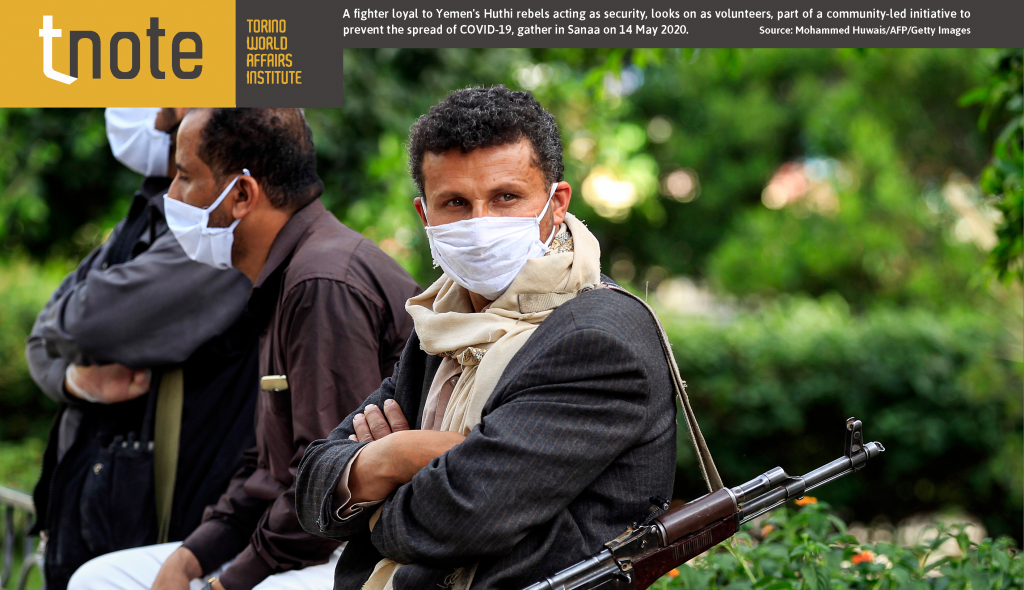

A fighter loyal to Yemen’s Huthi rebels acting as security, looks on as volunteers, part of a community-led initiative to prevent the spread of COVID-19, gather in Sanaa on 14 May 2020. Source: Mohammed Huwais/AFP/Getty Images.

The temporary nature of corona-ceasefires around the world underlines key findings from decades of research on armed conflict. First, it demonstrates that the drivers of violence are often complex, historically and structurally embedded, and multi-layered; truces that do not provide platforms to address these ‘conflict fault lines’ can at best only temporarily stall violence. Public health emergencies may provide opportunities to halt hostilities and begin negotiations, but to be sustained those efforts must be incorporated within a longer-term strategy addressing the drivers of conflict. Second, ceasefires can only lead to deeper forms of peace where there is political will and a degree of mutual trust. Studies show that peace processes have little success without overcoming these commitment problems, and in many cases, third-party actors may be critical. Where groups believe they can (or must) win the war, or perceive they can gain more through continued fighting than negotiation, ceasefires may themselves be perceived as a threat. Third, following the above, the observance of a ceasefire does necessarily indicate peaceable motives. In fact, ceasefires are sometimes directly linked to advancing war aims and may represent useful strategies for both state and non-state groups. Ceasefires may buy time, providing an opportunity to regroup and rearm, or may hold propaganda value in promoting a public image of being ‘pro-peace’ when there is no intention or expectation of having to follow through.

Where non-state groups have provided welfare during the pandemic, these actions may likewise point to their considerable propaganda value, rather than signalling peaceful intent. Coronavirus measures taken by non-state armed groups were reported around the world, often contrasting with perceived failures of state authorities. In Afghanistan, the Taliban implemented its own public health programme of awareness-raising and enforced temperature checks, documented in videos shared via social media. Criminal groups followed suit. In the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, traffickers enforced curfews and handwashing measures in communities under their control. In Mexico, cartels staged photo-ops of the delivery of their branded aid to civilians. In Cape Town, rival gangs were reported to have agreed a truce and begun delivering food parcels in their communities. Mafias and organised criminal groups in Italy and Japan provided food, loans and other welfare assistance to those in desperate need. Yet in all cases, these activities were far from purely altruistic.

Winning civilian support or compliance is vital for many armed groups; acts that encourage this can protect a group’s operations by deterring civilian cooperation with enemies, provide access to civilian intelligence, and generally bolstering popular support. A growing literature on rebel governance has shown how provision of welfare services can greatly benefit insurgent groups. Criminal groups, likewise, engage in forms of governance by leveraging provision of services and control of violence to strengthen relationships with civilians. During the pandemic, the actions of the Taliban, al-Shabaab, cartels in Mexico, trafficking groups in Brazil, and street-gangs in South Africa, can all be seen through this lens, which suggests that far from being a move towards peace, these responses are designed to strengthen these groups in the long-term.

The pandemic has also represented an economic opportunity for some groups. Whilst some have adapted their operations and have been hindered by strict lockdown measures, others have profited from increased demand for health products, food and illicit goods. In Cape Town, the street value of black-market tobacco and alcohol dramatically increased after the government banned their sale. Gangs profited from these lucrative markets and may ultimately emerge from the pandemic in a much stronger position. Indeed, the local truces in Cape Town were quickly undermined as lockdown measures were eased; street shootings, bloody feuds and battles over territory resumed. Ultimately, although the violent turf wars that accompany the global narcotics market may have temporarily abated in some places, the market’s core violence-driving logic remains untouched: drugs are lucrative and, for many groups, worth fighting over.

As countries begin to ease pandemic measures, the impact on peace and security will become clearer. This is an impact that cannot be assessed by short-term effects of ceasefires, or the apparently altruistic aid programmes run by non-state groups. As Lesley-Ann Daniels argues, the relevant question remains ‘whether the Coronavirus can change the dynamics of conflict to make peace more likely’. Early indications are not promising. Because ceasefires have not addressed the causes of violence and their various economic and political logics, it is unlikely that these alone can provide the basis for a pivot towards peace in conflict zones. Peacebuilding requires long-term and sustained efforts at all levels, and in some cases may be complicated by the ways in which armed groups have strengthened their position through their response to the pandemic.

Author

Kieran Mitton is Senior Lecturer in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London and co-founder of the Urban Violence Research Network.

Download

Corso Valdocco 2, 10122 Torino, Italy

Sede legale: Galleria S. Federico 16, 10121 Torino

Copyright © 2025. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved