Ebola at the frontier is an invisible enemy that causes non-traditional insecurities ranging from state neglect and draconian quarantines to starvation, conflict triggered by deprivations, and cross-border crises. Ebola is a lethal disease, in some situations having a 90% fatality rate, with horrific symptoms including high fever, diarrhoea and profuse internal and external bleeding. Because Ebola can also be relevant to bio-insecurity through bioterrorism, it creates security concerns and prompts policies that lead to the seclusion of the suffering bodies. In a bid to prevent the spread of Ebola, states close borders and raise barriers at national boundaries. Consequently, borderland people get caught up in deplorable crises beyond the epidemics themselves: local people face serious undocumented human insecurity. Draconian quarantines, for instance, produce food shortages when the movement of goods and services is restricted. Local people thus stop fighting against Ebola and start fighting for survival.

News of Ebola outbreaks leads to rejection, fear and panic among both national and international audiences. States focus on the external threats and vulnerabilities imposed by Ebola, managing the movements of human bodies and the well-being of the national population. National security capacity, therefore, is focused on ensuring citizens’ safety from external attacks brought about by infection with a deadly virus: when governments suspect the virus may enter their territory from another country, health matters turn into security matters and security measures are instituted to ensure that the virus does not enter the healthy body – in this case, the state. The assumption is that Ebola comes from outside, not from within, and policies are thus established to restrict the movement of people who are suspected of being carriers of the virus within and across national borders.

This T.note discusses some of the human security implications for individuals caught up in the crisis of an epidemic event in the borderlands of Uganda. It is the result of twelve months’ ethnographic fieldwork during research for an anthropological PhD on The constructions of Ebola and the struggle against the epidemic in Bundibugyo.

In 2007, the Bundibugyo District, approximately 360 kilometres to the west of Kampala, was one of the epicentres of an Ebola outbreak. The number of people who died in the mountains remained undocumented; however, more than 140 people were infected, of whom forty were recorded as having died. Bundibugyo lies west of the Rwenzori Mountains, alongside the international border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The district’s two main ethnic groups are the Bamba and the Bakonzo, both of which share ethnic and family ties with the people of the DRC. Most people in Bundibugyo possess kin and friends or people with whom they have affinity ties in the DRC, whom they rely on for social support. People in Uganda, for example, assist their relatives from the DRC to access both formal and informal institutions in Uganda. Communities across the border establish an interdependence on health care services that overlooks the customs and formal state border barriers. As a result, border communities seek help and move anywhere possible to receive medical and health care support, including by crossing borders during epidemic emergencies, as happened in 2007.

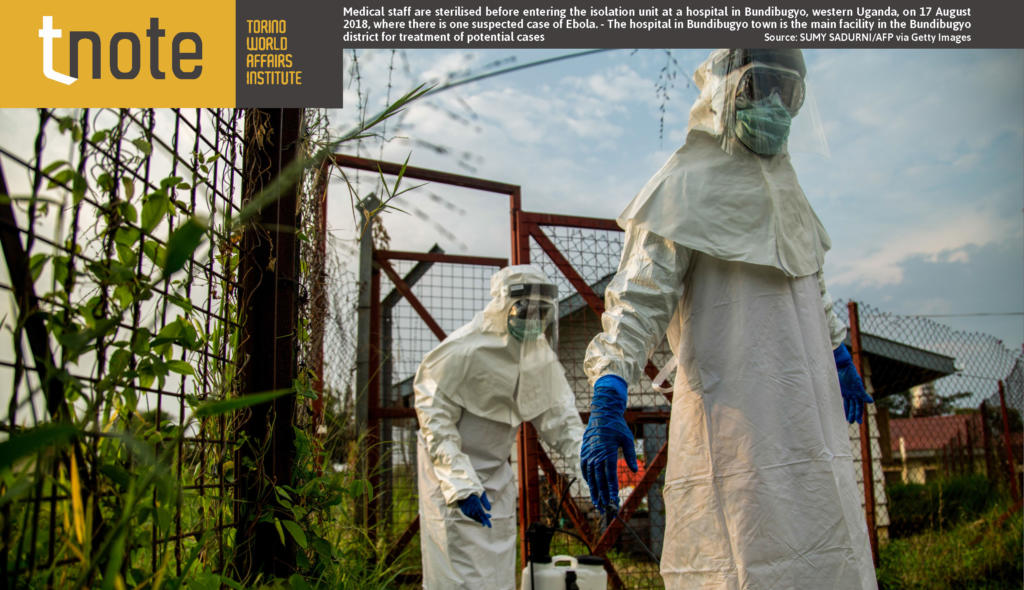

Medical staff are sterilised before entering the isolation unit at a hospital in Bundibugyo, western Uganda, on 17 August 2018, where there is one suspected case of Ebola. – The hospital in Bundibugyo town is the main facility in the Bundibugyo district for treatment of potential cases. Source: SUMY SADURNI/AFP via Getty Images.

When the 2007 epidemic started there was a three-month time lag before the experts responded and named it Bundibugyo Ebolavirus. In the meantime, untold fear and panic spread among the local communities, as people did not know what was killing them. An Ebola survivor in Nyahuka said that ‘While the epidemic started in August 2007, the medical team from Kampala came in November 2007, by the time the medical team from Kampala came, people had moved across the border from the mountain to the forest seeking all the help they could get’. The delayed emergency response demonstrated the government’s ill-preparedness in coordinating timely measures to address epidemic outbreaks in remote and isolated borderlands such as Bundibugyo – a district that even before the epidemic suffered from a combination of inadequate facilities and infrastructures. For three months there had been no monitoring or control measures, while cross-border movement of people had continued, exposing residents to considerable health risk. Only with the Ebola declaration were restrictions and controls on movement of people in Bundibugyo instituted: anybody suspected of being infected with Ebola was not allowed to move from their village; and in a situation when there was an Ebola-infected person in the family, the whole family and their entire village were confined for twenty-one days.

Entire communities turned into confinement camps and Bundibugyo was completely isolated. There was no bridge between the sick individuals in an ‘Ebola village’ in the district and their family members elsewhere. In other words, individuals from Bundibugyo ceased to be people with personality and identity and turned into sick bodies carrying a dangerous virus that could affect other citizens. People who tried to travel from the district were hunted down and rushed into isolation units for twenty-one days. When someone died during the outbreak, the corpse was buried solely by health officials without the approval of the deceased person’s family members.

Bundibugyo and its inhabitants were subjected to a prolonged period of stigma and rejection, not only by Uganda but also by neighbouring states. Neighbouring countries such as the DRC and Rwanda closed their borders to ensure that Ebola did not spill over into their territories. This created a scuffle in the borderland communities who depended on each other for daily survival. The border became a battleground for the immigration officers and public health experts who tried to control the movement of people. Closing the border escalated the outbreak emergency into a border crisis. An elder interviewed in Bubandi stated that ‘Closing the border was a bad decision because people seek strong traditional healing from the DRC. Other people have their ancestral homes in the DRC, where they go for healing in the case of a strange illness like Ebola. Again, the DRC has a lot of virgin forests, with herbs, people also believe that going to the DRC prevents witches in Bundibugyo from tracing them. So, relatives wanted to take ill individuals to the DRC for proper ritual treatment’.

The closure of the border produced a biolegitimacy controversy: the right of the suffering body to cross the border cannot apply to the Ebola situation. In normal circumstances it is indeed morally acceptable for an ill person to move from their country and go to any other place where treatment can be obtained, but an Ebola victim cannot go to another country to seek medical help. This may sound logical, but the people in the borderlands do not recognize the borderlines that formally prevent their relatives from receiving treatment across the border or from making cross-border visits for any other reason. Additionally, in 2007 several Ugandans who wanted to travel to other countries were denied visas, while Ugandan Muslims were refused permission to go to Mecca to make the religious pilgrim called hajj that year.

Bundibugyo natives, in particular, were considered disease carriers and perceived as a national threat – not as individuals but as diseased bodies. Travellers from the areas marked contaminated ceased to be humans and were considered to be bodies carrying something alien – a virus, bugs, parasites, germs, and worms – to which the state must deny access.

Ebola created mental barriers between contaminated and ‘clean’ regions that raised national security concerns. These barriers stripped people of their identity – they became viruses themselves – and of their social ties, keeping families and communities apart.

Although divided by an artificial line, borderland people are one group: ‘border-landers’. Even in the middle of an outbreak, they should be allowed to determine their own interests, aspirations and security. At the frontier, human security should take precedence over national security, and states – especially neighbouring ones – should work collectively to alleviate the common invisible enemy that is the Ebola virus, using a regional cooperation approach, rather than closing their borders and causing a human security crisis for the borderlands.

Author

Jerome Ntege is Social Anthropology lecturer at Makerere University and Kyambogo University.

Download

Copyright © 2025. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved