On January 28, 2018 representatives from eleven countries, following the strong leadership of Japan and Australia, agreed to a modified version of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). This new pact – renamed the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTTP), or TPP 11 – will take effect upon ratification by at least six member countries. Expectations are that this will occur sometime in 2019. The CPTPP agreement represented a major recovery by the eleven countries following initial expectations that TPP was dead after the election of Donald Trump.

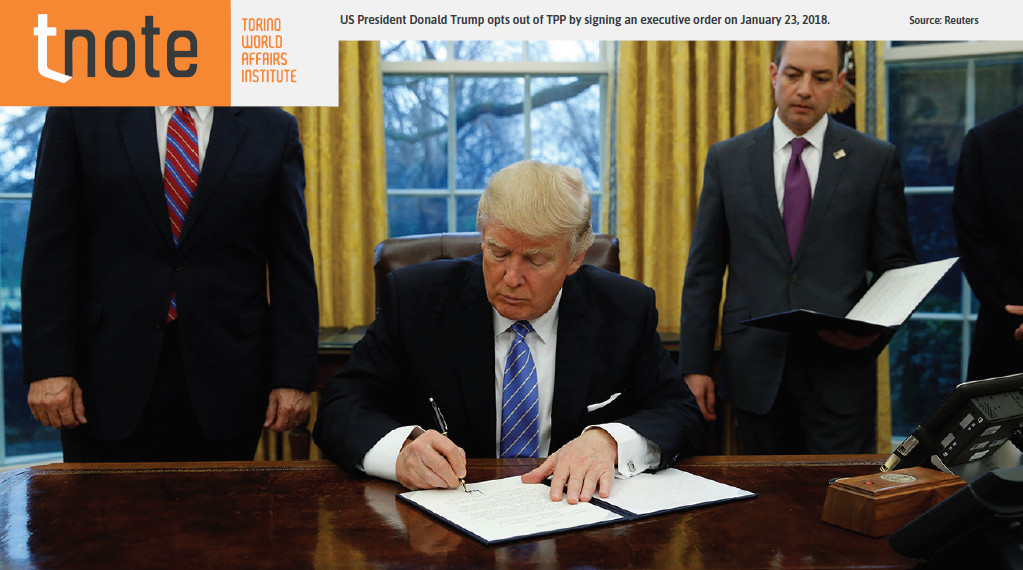

Trump, as an early follow through on his xenophobic campaign promises of a unilateral America, signed an executive order pulling the US out of the TPP within one hundred hours of being sworn into office. With that stroke of his pen, Trump wiped out 10 years of labor on the so-called “Pacific” route to regional trade integration, anchored on the US market. His actions also defied multiple economic analyses emphasizing the strong economic benefits that TPP would provide for the US economy. Turmoil immediately prevailed among the remaining eleven signatories.

Chaos over trade is only one of the challenges now threatening to upend the stable economic and security order that has prevailed in the Asia-Pacific from the early 1980s until the early 2010s. For roughly thirty years, the regional order was defined primarily by increased economic interdependence, rising institutional multilateralism, and the absence of state-to-state military conflicts. Challenges to that tranquil order were by no means absent, but most pale in significance to the far more ominous challenges to both intra-regional economic and security stability now emerging. None is potentially more upending of stability than the American pull-back from regional engagement since the Trump administration took office.

TPP was the most ambitious of the burgeoning regional trade agreements designed to advance free trade as a way to offset the stagnation of the Doha Round of global trade negotiations. As it had evolved by 2016, TPP promised monumental changes to the existing Asia-Pacific trade regime in four central ways. First, as the most comprehensive and ambitious regional trade agreement the US had ever concluded, it was the centerpiece of the Obama administration’s multidimensional “pivot” or “repositioning toward Asia”. Second, TPP represented a monumental shift by several Asian governments against domestic political protectionism and instead embracing extensive trade liberalization measures they had long opposed. Third, TPP promised “high quality” and “ambitious” “21st Century standards” for trade, ambiguous as those terms remained. TPP was designed to reach well “behind the border” in ways that traditional tariff reductions had not. Fourth and finally, though less often the lead item in TPP press releases, the trade pact would address many of the geo-strategic interests of the signatories. The TPP explicitly excluded China, convincing both the US and many of the other eleven partners that the trade pact had not just commercial, but also security, benefits. In all of these ways TPP promised a vehicle by which key Asian trading partners could retain close economic and security ties with the US while simultaneously bolstering the global liberal order within the region.

The Obama administration took office convinced that America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan mistakenly focused on non-existential threats that deflected both Treasury resources and senior policymakers’ attention away from the more strategically and economically critical Asia-Pacific. Asia has become the economic heavyweight of the globe, accounting for 60 percent of global GDP and nearly half of the world’s international trade. Not at all coincidentally, it would be to America’s distinct advantage if the US could structure the major trade architecture of the Asia-Pacific. As President Obama once wrote in a Washington Post defense of TPP: “The world has changed. The rules are changing with it. The United States, not countries like China, should write them. Let’s seize this opportunity, pass the Trans-Pacific Partnership and make sure America isn’t holding the bag, but holding the pen”.

What had therefore been developing as a fulsome reinforcement of the liberal trade order within the Asia-Pacific was shattered by the election of Donald Trump and his commitment to obliterate every vestige of the Obama administration. Trump ran a campaign of full-throated white nativist populism, a central component of which was the antagonism to the global liberal order, represented among other things by TPP. Of particular centrality to Trump’s antagonism were bilateral trade deficits. These he portrayed in starkly Manichean terms: American was “winning” when its exports to any single country were greater than its imports from that country; if the equation was reversed, the US was “losing”. Since the US bilateral trade balance with most countries had long been negative (in goods, though often not in services, a distinction he and his supporters conveniently ignored), the global trading system as organized under the WTO and most multilateral trade agreements such as NAFTA, KORUS, and TPP, were collectively “taking advantage of the United States”. His solution was to demand “a better deal for America” by challenging all existing multilateral arrangements and/or replacing them with renegotiated bilateral trade deals. In March 2018 he went so far as to risk a global trade war by imposing unilateral tariffs on steel and aluminum, presumably in expectation that these would force various trade partners to rectify their “unbalanced” trade by entering into bilateral negotiations.

Populist nationalism also helps explain the administration’s general disdain for engaging in nuanced foreign policy analysis and for the Asia-Pacific as a geographical priority. Thus, after eighteen months in office, hundreds of key administrative appointments in diplomacy and foreign policy remain unfilled, including key positions dealing with East Asia, while the Department of State budget has been slashed. The decision to withdraw the US from TPP is therefore but one trade specific component of the broader self-isolation of the US from the Asia-Pacific more generally.

European nations are now struggling to forge some collective strategy to preserve the global trade order in the face of a unilateral and isolationist US. On the other side of the globe, the remaining eleven signatories to the revised TPP are seeking to prop up the liberal trade order in the Asia-Pacific. It is not clear whether or not they will resist American protectionism long enough to allow a new American administration to take over and re-commit the country to its more traditional globalized perspective or whether the damage that the Trump administration is inflicting will prove beyond repair. Yet, at present, cooperation among the TPP 11 is East Asia’s best hope for continuing to preserve the global trade order.

Download

Copyright © 2025. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved